When a generic drug company wants to prove its version of a medication works just like the brand-name version, it doesn’t test it on thousands of people. It uses a smarter, leaner method: the crossover trial design. This isn’t just a statistical trick-it’s the backbone of how regulators like the FDA and EMA decide if a generic drug is safe and effective enough to hit the market. And it’s used in nearly 9 out of 10 bioequivalence studies approved today.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence

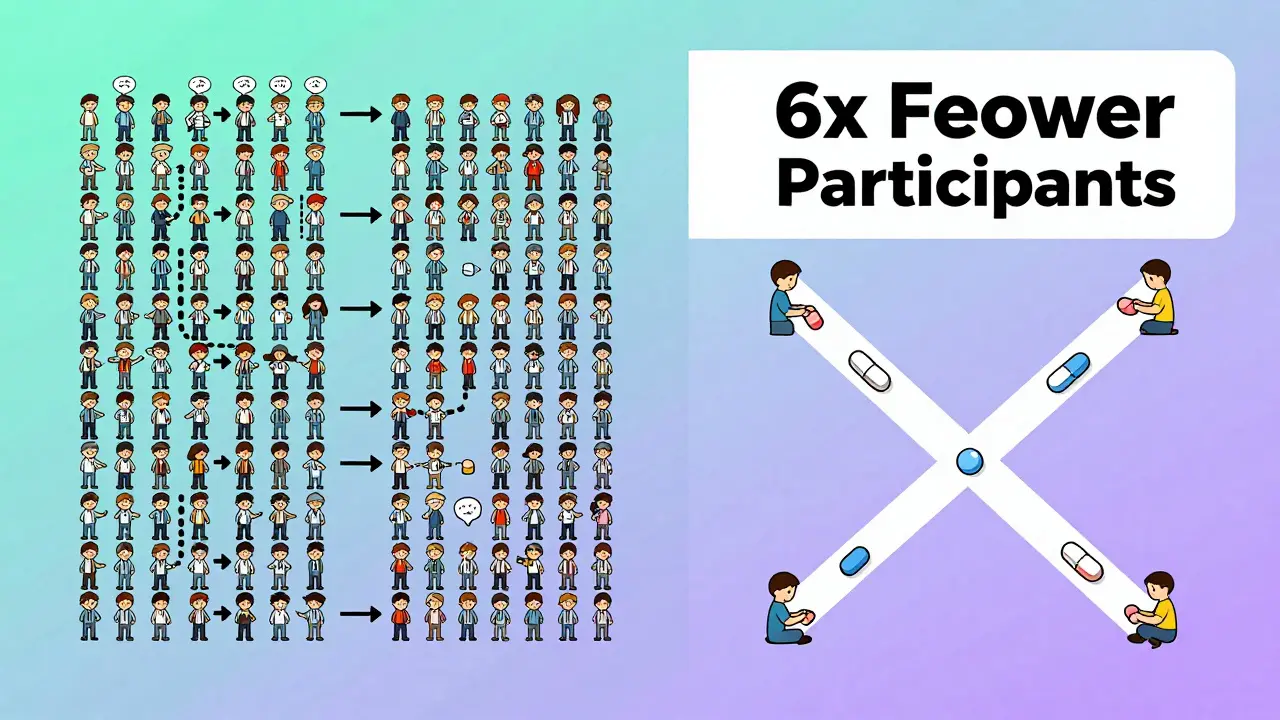

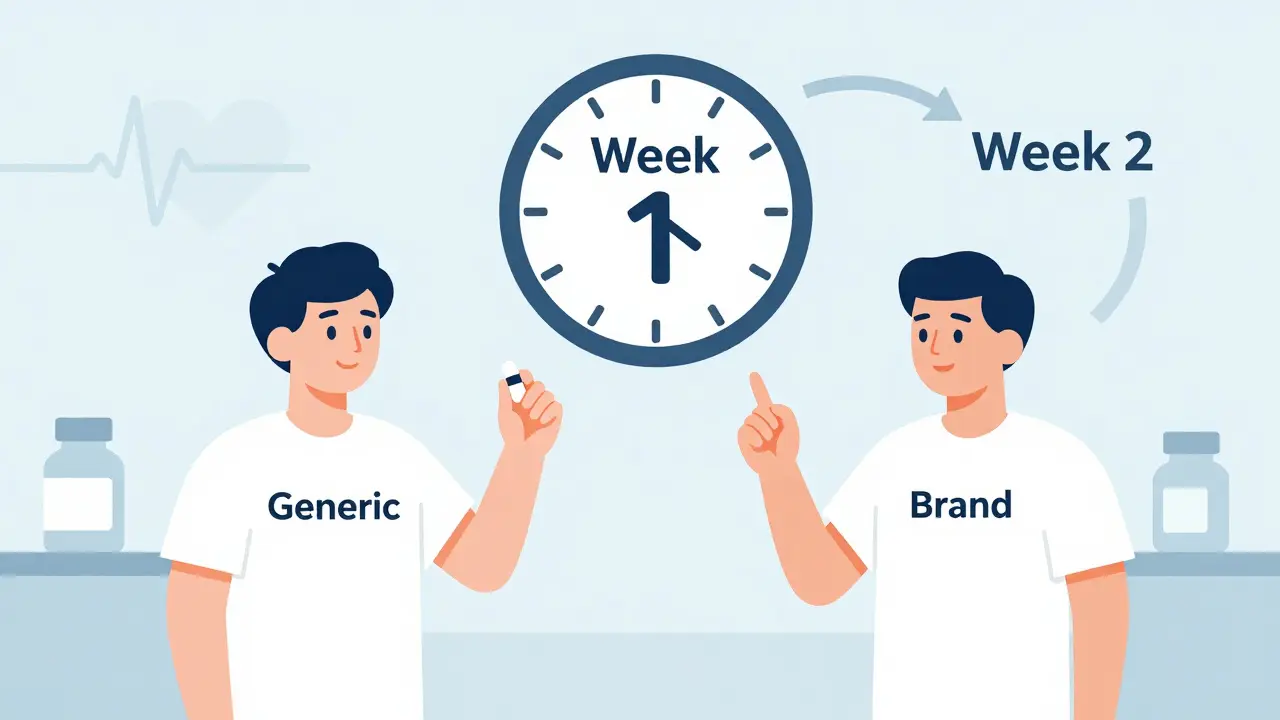

Imagine you’re testing two different painkillers. In a normal study, you’d give one group Drug A and another group Drug B, then compare results. But people are different-some metabolize drugs faster, some have higher body weight, some are just naturally more sensitive. That noise makes it harder to tell if the drugs are truly the same. A crossover design solves this by having each person take both drugs. One week they take the generic, the next week they take the brand-name version. Their own body becomes the control. That cuts out the noise from person-to-person differences. The result? You can use far fewer people to get the same level of confidence. Studies show that when between-person variability is twice as high as measurement error, a crossover design needs only one-sixth the number of participants compared to a parallel study. That means fewer people, lower costs, faster results. For a typical bioequivalence study, that’s often 24 people instead of 144.The Standard: 2×2 Crossover Design

The most common setup is called the 2×2 crossover. Here’s how it works:- Participants are split into two groups randomly.

- Group A gets the test drug first (T), then after a washout, the reference drug (R).

- Group B gets the reference drug first (R), then the test drug (T).

What Happens When the Drug Is Highly Variable?

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or clopidogrel, have wide swings in how they’re absorbed from person to person. These are called highly variable drugs (HVDs), defined by an intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) over 30%. For HVDs, the standard 2×2 design falls apart. Even with 72 people, you might not have enough power to detect a difference. That’s where replicate designs come in. There are two types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Each person gets the test drug once and the reference drug twice.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Each person gets both drugs twice.

Statistical Analysis: What the Numbers Really Mean

It’s not enough to just give people the drugs. You have to analyze the data right. The gold standard is a linear mixed-effects model using software like SAS or Phoenix WinNonlin. The model checks three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order of drugs affect results? (Should be no.)

- Period effect: Did time itself change outcomes? (Like seasonal changes or fatigue.)

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between test and reference?

When Crossover Designs Fail-and Why

Crossover trials aren’t magic. They have pitfalls. One common mistake? Underestimating the washout period. A 2021 case on ResearchGate involved a study that failed because the washout was only three half-lives. Residual drug was still detectable in period two. The sponsor had to restart with a 4-period replicate design-costing an extra $195,000. Another issue? Carryover effects. Even with proper washout, some drugs linger in tissues or affect metabolism long-term. Statisticians test for sequence-by-treatment interaction to catch this. If it’s significant, the study is invalid. And let’s not forget the human factor. Some people remember how they felt during the first period and change their behavior in the second-consciously or not. That’s why double-blinding is non-negotiable. Everyone, including the participants, must believe they’re getting the same thing each time.

Real-World Impact: Costs, Time, and Success Rates

The savings aren’t theoretical. In 2022, a generic warfarin study saved $287,000 and eight weeks by using a 2×2 crossover instead of a parallel design. That’s money that goes into making the drug affordable. But replicate designs cost more. Adding two extra treatment periods means more blood draws, more clinic visits, more staff time. Industry surveys show they add 30-40% to study costs. But they also cut failure rates by nearly 70% for HVDs. And failure means delays. A rejected bioequivalence study can push a generic drug launch back by a year. That’s lost revenue for manufacturers and delayed access for patients.What’s Next? The Future of Bioequivalence

Regulators are adapting. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows 3-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs-like anticoagulants or anti-seizure meds-where even small differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to make full replicate designs the standard for all HVDs in 2024. Meanwhile, adaptive designs are rising. Some studies now use a two-stage approach: start with 12 people, check the data, then decide whether to add more. That’s more efficient than guessing sample size upfront. The biggest threat? Not to the design itself, but to its assumptions. Digital health tools now let us track drug levels continuously with wearable sensors. If we can monitor concentrations in real time, maybe we won’t need long washouts. Maybe we can do multiple doses in a single day. But for now, the crossover design is still king. It’s proven, regulated, and trusted. As Dr. Donald Schuirmann, a co-developer of RSABE, put it: “Crossover designs will remain the gold standard through 2035.”Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control. This removes variability between individuals-like differences in age, weight, or metabolism-making it easier to detect true differences between drugs. As a result, crossover designs need far fewer participants than parallel studies to achieve the same statistical power.

Why is a washout period necessary in a crossover trial?

A washout period ensures that the drug from the first treatment period is completely cleared from the body before the next one begins. If traces remain, they can interfere with the results of the second treatment, creating a carryover effect. Regulatory guidelines require at least five elimination half-lives between periods to ensure concentrations fall below detectable levels.

When is a replicate crossover design used instead of a 2×2 design?

Replicate designs (TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) are used for highly variable drugs-those with an intra-subject coefficient of variation over 30%. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which widens the acceptable bioequivalence range and avoids requiring impossibly large sample sizes in standard designs.

What are the most common reasons bioequivalence studies fail?

The most common reason is inadequate washout periods leading to carryover effects. Other major issues include improper statistical analysis, failure to account for period effects, missing data from dropouts, and lack of proper blinding. Studies with sequence-by-treatment interaction effects are typically rejected.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives-like those lasting more than two weeks-because the required washout period would be impractical. In these cases, parallel designs are required. They’re also avoided for drugs with irreversible effects or those used to treat chronic conditions where stopping treatment is unsafe.

Medications

Medications

Thomas Anderson

December 15, 2025 AT 21:58So basically, crossover designs let you test two drugs on the same person and cut the participant count by like 80%? That’s wild. No wonder generics are cheaper - it’s not because they’re low quality, it’s because the science is smart.

Daniel Wevik

December 17, 2025 AT 05:36Let’s not romanticize this - the 2x2 crossover is elegant, but it’s built on assumptions that break down with HVDs. The moment you get intra-subject CV >30%, you’re playing Russian roulette with statistical power. That’s why the industry’s shifting to replicate designs - it’s not preference, it’s necessity.

Dwayne hiers

December 17, 2025 AT 11:52For anyone reading this and thinking ‘why not just use a parallel design?’ - you’re ignoring the statistical efficiency. The linear mixed-effects model with REML estimation for sequence, period, and treatment effects is non-negotiable. SAS PROC MIXED or WinNonlin’s mixed model module is the gold standard. Skip the ANOVA - it’s outdated and underpowered for crossover data.

Also, don’t forget: the 90% CI for AUC and Cmax must be within 80–125% on the log scale. Not arithmetic, not raw - log-transformed. That’s where people mess up in regulatory submissions.

Rulich Pretorius

December 17, 2025 AT 20:49It’s fascinating how a method rooted in minimizing human variability ends up being the most humane approach. Fewer participants means less burden on volunteers. Fewer blood draws. Shorter clinic visits. The design doesn’t just save money - it respects the people who make the science possible.

And yet, we still treat these trials like black boxes. The public sees ‘generic drug approved’ and assumes corner-cutting. No one realizes the precision behind it - the washout periods, the blinding, the statistical rigor. We owe these volunteers more than indifference.

Rich Robertson

December 18, 2025 AT 07:21As someone who’s watched this from both sides - clinical trial coordinator and patient advocate - I’ve seen how these designs shape real lives. A warfarin generic approved six months early? That’s someone in rural Ohio getting their blood thinner for $12 instead of $300. This isn’t just stats. It’s access.

And the replicate designs? They’re not just for HVDs anymore. With biologics and complex generics on the horizon, we’re going to need them even more. The FDA’s 2023 draft is a step in the right direction.

jeremy carroll

December 19, 2025 AT 18:20bro i had a friend do a bioequiv study and they messed up the washout and had to restart. like… 5 half lives? that’s like 3 weeks for some stuff. imagine paying for 144 people and then realizing you forgot to wait long enough. oof.

Tim Bartik

December 20, 2025 AT 08:29US and EU let generics in with this system? Pathetic. In China they test on 500 people minimum. Real science. This crossover nonsense is just corporate cost-cutting dressed up as innovation. You think a 24-person study tells you anything about real-world use? Wake up.

Sinéad Griffin

December 21, 2025 AT 03:59the fact that we’re even having this conversation is wild. 🤯 imagine if we used this same logic for vaccines. ‘oh we only need 24 people to test if it works!’ nope. not happening. but for pills? sure. let’s gamble with people’s lives. 🙄

Edward Stevens

December 22, 2025 AT 10:49So let me get this straight - we’re using a design that relies on people being perfectly consistent over weeks, with perfect blinding, zero carryover, and no dropout… and we call this ‘robust’? I’ve seen studies where people forgot which pill they took and started eating more salt in week two because they thought they were on the ‘placebo.’

It’s not science. It’s a very expensive game of telephone.

Daniel Thompson

December 23, 2025 AT 03:37The assumption that subjects are homogenous across periods is flawed. Psychological priming, circadian rhythm shifts, dietary changes - all confounders. The regulatory agencies are aware, yet they still accept these studies. Why? Because the cost of rejecting them is higher than the cost of occasional false positives.

Transparency is the missing piece. Raw data, statistical code, and subject-level results should be public. But they’re not. And that’s not science - that’s opacity disguised as efficiency.

Alexis Wright

December 24, 2025 AT 14:02Let’s be honest: this entire system is a Ponzi scheme disguised as regulatory science. The FDA and EMA don’t care about efficacy - they care about approval rates. Crossover designs are the perfect tool for this: small N, high variance, low transparency. The ‘80–125%’ range is a joke. That’s a 45% window of acceptable difference. You wouldn’t accept that for your phone charger - why for your heart medication?

And don’t even get me started on RSABE. It’s not science - it’s regulatory surrender. They’re just widening the gap until the drug ‘looks’ equivalent. It’s corporate capture wrapped in statistical jargon.

Dr. Schuirmann? He’s not a hero. He’s a collaborator in the system that lets billion-dollar pharma companies profit off half-tested generics. Wake up.

Natalie Koeber

December 24, 2025 AT 15:36you know what’s sus? they say washout is 5 half-lives… but what if the drug accumulates in fat tissue? what if the ‘washout’ is just a placebo for the body? what if the FDA is in cahoots with big pharma to hide how these drugs really behave? i’ve read papers where residual drug was found 10 days later… they just ignore it. #crossoverconspiracy

Wade Mercer

December 26, 2025 AT 14:13It’s not just about cost - it’s about ethics. If a drug’s effects are too unpredictable or dangerous to test on the same person twice, then it shouldn’t be approved as a generic. Period. This isn’t a math problem - it’s a moral one. If the body can’t reset, then the drug shouldn’t be on the market.

Jonny Moran

December 27, 2025 AT 10:40For anyone new to this - don’t get overwhelmed. The crossover design is just a tool. It’s not perfect, but it’s the best we’ve got for now. The real win? It makes life-saving meds affordable. That’s not magic. That’s good science doing good work.

And yes, the replicate designs are expensive - but they’re worth it. They’re the reason we’re getting generics for warfarin, clopidogrel, and now even some biologics. Keep pushing for better methods, but don’t trash the ones that already save lives.

Rulich Pretorius

December 27, 2025 AT 11:52That’s exactly why we need to invest in real-time monitoring tech. If wearables can track plasma concentrations continuously, we might not need washouts at all. Imagine a single day with multiple doses - each monitored via patch. That’s the future. The crossover design isn’t the end - it’s the bridge.