Malaria Risk Assessment Calculator

Enter your details and click "Assess Your Risk" to see your malaria risk level.

TL;DR

- Malaria is rare in the US, with roughly 1,500 cases reported annually, almost all imported.

- Most infections come from travelers returning from sub‑Saharan Africa or South‑East Asia.

- The native mosquito species capable of transmission are limited to a few southern states.

- Prompt diagnosis and appropriate drug treatment prevent severe disease.

- Travelers should use CDC‑recommended chemoprophylaxis and bite‑prevention measures.

When you hear the phrase malaria in the United States, you probably picture swarms of mosquitoes and endless fevers. In reality, the picture is far more nuanced. Below we break down what malaria really looks like on American soil, who’s at risk, and what you can do to stay safe whether you live here or are just passing through.

Malaria in the United States is a public‑health condition defined by the occasional appearance of Plasmodium‑infected individuals within U.S. borders, most often linked to recent international travel rather than local transmission. The disease is monitored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and reported to state health departments for rapid response.

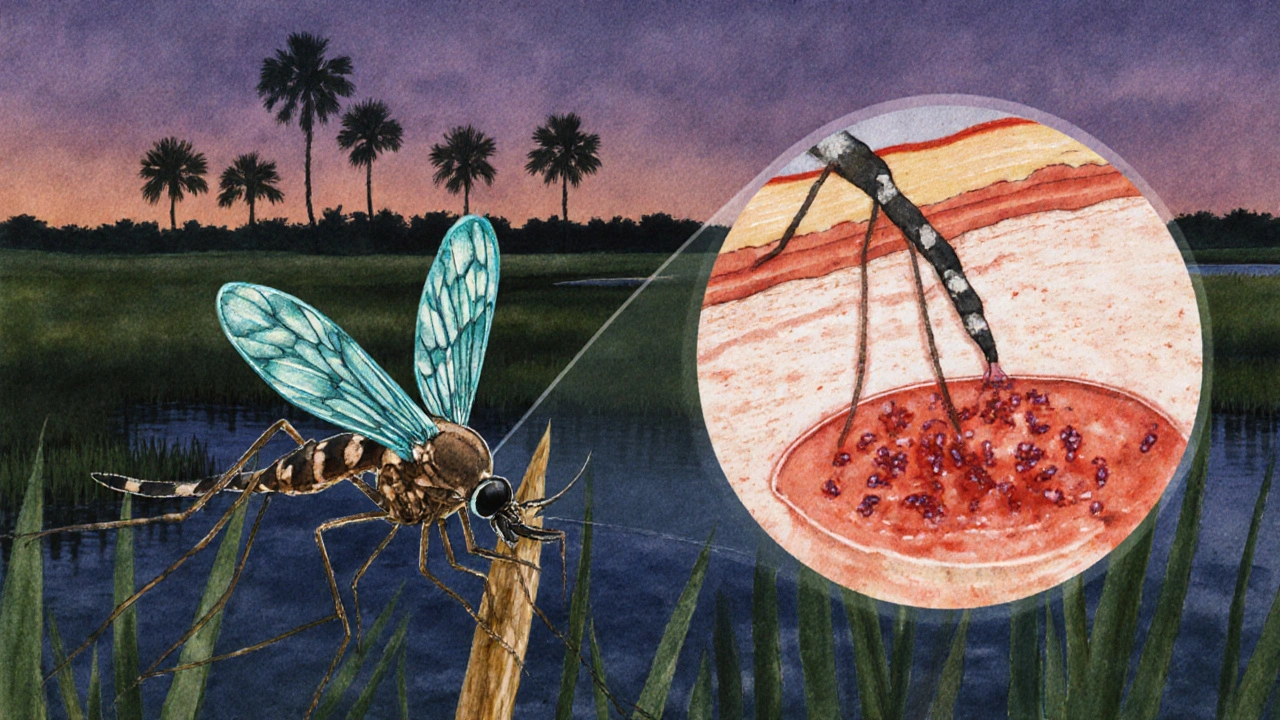

What Exactly Is Malaria?

Malaria is a blood‑borne infection caused by Plasmodium parasites. The five species that infect humans-P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi-vary in severity and geographic distribution. In the United States, the overwhelming majority of cases involve P. falciparum and P. vivax because these are the species most common in Africa and Asia, the regions most traveled by Americans.

Current Epidemiology: Numbers and Trends

According to the CDC’s annual malaria surveillance report, the United States recorded 1,473 cases in 2023, 1,538 in 2024, and 1,502 in the first nine months of 2025. That steadiness masks a clear pattern: over 95% of cases are imported, with only a handful (usually fewer than five per year) linked to local mosquito‑borne transmission.

Geographically, imported cases cluster in large metropolitan areas (New York, Los Angeles, Chicago) reflecting travel volume. The handful of locally acquired infections have all come from the Gulf Coast-primarily Florida, Texas, and Arizona-where resident Anopheles mosquitoes can act as vectors under warm, humid conditions.

How Do Cases Arrive?

Three pathways dominate:

- International travel: Tourists, business travelers, military personnel, and immigrants returning from endemic regions bring parasites in their bloodstream.

- Blood transfusion: Though rare, malaria can survive in donated blood; strict screening has reduced this risk dramatically.

- Local transmission: In the few southern counties where competent Anopheles species persist, an infected traveler can seed a limited outbreak if mosquitoes bite them and later bite a local resident.

The CDC operates an “airport screening” program at major international hubs. While the program does not stop all imported cases, it helps flag high‑risk individuals for early testing.

Key Vectors and Species Present in the U.S.

Only a subset of the roughly 40 North American Anopheles species can transmit malaria, with Anopheles quadrimaculatus and Anopheles freeborni being the most competent. Their distribution is limited to the southeastern United States and parts of the Pacific Northwest, respectively. Even where they exist, seasonal temperature thresholds (≈18°C) constrain transmission to the summer months.

Diagnosing Malaria Quickly

Early diagnosis saves lives. The standard work‑up includes:

- Microscopic blood smear: The gold standard; technicians count parasites per microliter to gauge severity.

- Rapid diagnostic test (RDT): Detects Plasmodium antigen; useful in settings without microscopy.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): Confirms species, especially when mixed infections are suspected.

Hospitals with emergency departments near international airports typically have RDT kits on hand, while larger academic centers maintain full microscopy capability.

Treatment Options and Prophylaxis Comparison

Once malaria is confirmed, treatment depends on species and severity. For uncomplicated P. falciparum, the CDC recommends an artemisinin‑based combination therapy (ACT) such as artemether‑lumefantrine. Severe cases require intravenous artesunate.

Travelers can prevent infection by taking chemoprophylaxis before, during, and after their trip. Below is a side‑by‑side look at the three most commonly prescribed drugs.

| Drug | Typical Dose | Pros | Cons / Contra‑indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atovaquone/Proguanil (Malarone) | 1 tablet daily, start 1-2 days before travel | Well‑tolerated, works against all species, short post‑travel course | Higher cost, not preferred for severe hepatic disease |

| Doxycycline | 100mg daily, start 1-2 days before travel | Inexpensive, also prevents some bacterial infections | Photosensitivity, GI upset, not for pregnant women or children <12yr |

| Mefloquine | 250mg weekly, start 2-3 weeks before travel | Convenient weekly dosing, good for long trips | Neuropsychiatric side effects, contraindicated in patients with seizure disorders |

Pre‑Travel Prevention Checklist

- Schedule a visit to a travel medicine clinic at least 4weeks before departure.

- Choose a chemoprophylaxis regimen that fits your health profile and itinerary.

- Pack DEET‑based insect repellent, permethrin‑treated clothing, and a portable mosquito net.

- Stay in screened or air‑conditioned rooms; use bed nets only when necessary.

- Know the signs-fever, chills, headache, nausea-so you can seek care promptly after returning.

U.S. Public Health Response

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) coordinates nationwide surveillance through the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). When a case is reported, the CDC works with state health departments to:

Data from these investigations feed into annual reports that guide clinicians, travel agencies, and policy makers. Don’t wait for a fever to clear up on its own. If you’ve returned from a malaria‑endemic country in the past 30days and develop flu‑like symptoms, take these steps: Local transmission is exceedingly rare. Since 2000, fewer than 20 autochthonous cases have been documented, all in southern states where competent Anopheles mosquitoes exist and temperatures permit parasite development. For domestic travel within the continental United States, prophylaxis is not required. Focus instead on mosquito bite prevention (repellent, clothing). Prophylaxis is only advised for trips to endemic countries. The risk is extremely low. The American Red Cross and FDA require meticulous donor screening for travel to endemic areas. Cases are almost unheard of today. Pregnant women are generally advised to use Atovaquone/Proguanil if started before pregnancy, or to rely on strict bite‑prevention if exposure risk is low. Doxycycline and Mefloquine are contraindicated. Incubation periods vary by species: P. falciparum typically shows symptoms within 7-14 days, while P. vivax and P. ovale can remain dormant in the liver and cause illness up to 2years later. Understanding malaria’s place in the United States helps you stay ahead of the few but serious cases that do arise. With solid prevention habits, quick diagnostics, and the right drug regimen, you can travel confidently and protect your health at home.

What If You Suspect Malaria?

Frequently Asked Questions

Is malaria ever transmitted locally in the United States?

Do I need malaria prophylaxis for a short business trip to Florida?

Can I get malaria from a blood transfusion in the U.S.?

Which prophylaxis drug is best for pregnant travelers?

How long after returning from an endemic area can malaria appear?

Medications

Medications

Josh Grabenstein

October 3, 2025 AT 03:39Malaria numbers look clean but the data hides hidden vectors :)

Marilyn Decalo

October 8, 2025 AT 22:32Wow, you just dropped a bombshell on malaria stats! I can't believe how few cases we actually see here. The drama of imported cases is like a Hollywood thriller, with travelers as unsuspecting heroes. Yet the CDC quietly does its job, and we sit in awe.

Mary Louise Leonardo

October 14, 2025 AT 17:25They tell us malaria's rare, but have you ever wondered who’s really tracking those “imported” cases? Some say the numbers are filtered, hidden behind layers of bureaucracy. It feels like a circus where the clowns wear lab coats. I think there’s an agenda to downplay local mosquito threats. Stay skeptical, friends.

Alex Bennett

October 20, 2025 AT 12:19Interesting take, but let’s remember that most infections come from abroad, not backyard barbecues. If you’re heading to endemic zones, pack your meds-no need to panic over a few local bites. The CDC guidelines are solid, even if they read like a boring textbook. Chill out and follow the science.

Mica Massenburg

October 26, 2025 AT 06:12Sure, the CDC does its “quiet” work, but quiet can also mean invisible oversight. Sometimes the lack of loud warnings hides deeper problems. Just sayin’.

Sarah Brown

November 1, 2025 AT 01:05Let’s cut through the noise and focus on practical steps. First, get a pre‑travel consultation and discuss chemoprophylaxis options. Second, pack a good insect repellent and a bed net if you’ll be in high‑risk areas. Third, know the warning signs of malaria and seek care immediately if symptoms arise. Remember, preparation saves lives.

Max Canning

November 6, 2025 AT 19:59Yo, if you’re traveling, grab that meds and smash those mosquitoes! Adventure awaits, but don’t let malaria ruin the vibe.

Nick Rogers

November 12, 2025 AT 14:52Travelers, assess risk, choose prophylaxis, stay protected. Simple as that.

Tesia Hardy

November 18, 2025 AT 09:45Don't forget to double‑check your prescriptoin before you go. I once forgot mine and got really sick, it was a tough lesson. Stay safe and enjoy your trip!

Matt Quirie

November 24, 2025 AT 04:39Indeed, the epidemiological data underscores the predominance of imported cases; however, the potential for autochthonous transmission, albeit minimal, warrants vigilance; especially in southern jurisdictions where competent vectors persist.

Pat Davis

November 29, 2025 AT 23:32From a public health perspective, the United States’ surveillance mechanisms are commendable; yet, cross‑border collaboration with Canada could enhance early detection of emerging trends, particularly as climate patterns shift.

Mary Wrobel

December 5, 2025 AT 18:25Traveling? Pack your meds, slather on repellent, and keep those pesky mosquitoes at bay-your adventure deserves nothing less than a healthy you.

Lauren Ulm

December 11, 2025 AT 13:19We chase facts, yet shadows linger behind every statistic 🤔. If the CDC filters data, what else might be concealed? The truth is a puzzle, and each piece matters 🧩. Keep questioning, stay informed :)

Michael Mendelson

December 17, 2025 AT 08:12One mustn’t simply accept the superficial narrative; deep analysis reveals a tapestry of oversight, definetly not for the faint‑hearted. The elites of health policy often mask complexities behind glossy press releases. Wake up, sheeple.

Ibrahim Lawan

December 23, 2025 AT 03:05The data presented in the article provides a solid foundation for understanding malaria risk in the United States.

It correctly emphasizes that the overwhelming majority of cases are imported rather than locally transmitted.

This distinction is crucial for public health officials when allocating resources for surveillance and response.

Nevertheless, the presence of competent Anopheles species in certain southern counties should not be dismissed lightly.

Seasonal temperature thresholds mean that transmission potential, though limited, can re‑emerge under favorable climatic conditions.

Travelers to endemic regions must therefore adhere strictly to CDC‑recommended chemoprophylaxis regimens.

Antimalarial medication should be initiated before departure, continued throughout exposure, and maintained for the appropriate post‑travel period.

In addition to pharmacologic measures, personal protective strategies such as insecticide‑treated bed nets and DEET‑based repellents remain essential.

Early diagnosis relies on rapid diagnostic tests and microscopy, and health‑care providers should maintain a high index of suspicion when patients present with febrile illness after travel.

Prompt treatment with artemisinin‑based combination therapies has dramatically reduced mortality from severe Plasmodium falciparum infection.

Community education campaigns can further reduce risk by informing the public about symptom recognition and when to seek medical care.

Moreover, continued funding for vector surveillance programs will enable timely detection of any expansion of Anopheles habitats.

Collaborative research between entomologists, climatologists, and epidemiologists is needed to model future transmission scenarios under climate change.

Policymakers should consider integrating these projections into preparedness plans to mitigate potential outbreaks.

Finally, individual responsibility-being well‑informed, adhering to prophylaxis, and employing bite‑prevention-complements the broader public health effort.

In sum, while malaria remains rare in the United States, vigilance and proactive measures ensure that it stays that way.