Pharmacogenetic Risk Calculator

Have you ever taken a medication that made you feel worse instead of better? Maybe you got dizzy on a common blood pressure pill, or broke out in a rash from an antibiotic your friend took without issue. You weren’t unlucky-you might just have a genetic profile that makes your body react differently to drugs than most people. This isn’t rare. In fact, genetic factors are behind why some people suffer severe side effects while others don’t, even when they take the same dose of the same drug.

Why Your Genes Control How You React to Medicines

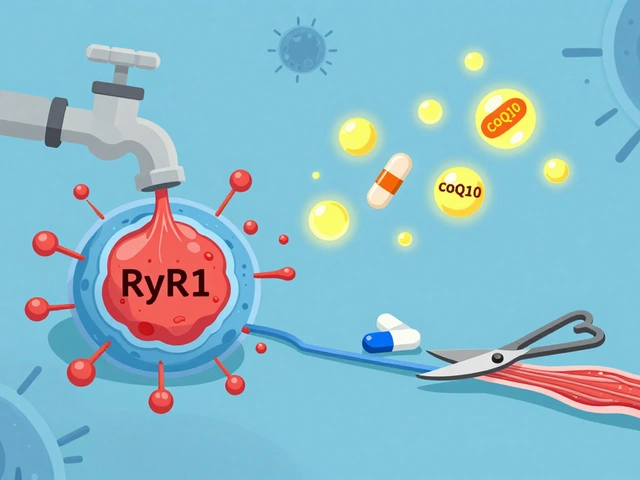

Your genes are like instruction manuals for how your body builds and runs its systems. When it comes to drugs, two big systems are controlled by your DNA: how fast your body breaks down the medicine, and how the medicine interacts with your cells. If either of these systems runs too fast, too slow, or just differently, side effects happen. For example, the CYP2D6 gene tells your liver how to process over 25% of all prescription drugs, including antidepressants, painkillers like codeine, and even tamoxifen for breast cancer. Some people have a version of this gene that makes them ultrarapid metabolizers-they turn codeine into morphine so quickly it can cause dangerous breathing problems, especially in babies if the mother is breastfeeding. Others are poor metabolizers-they barely break it down at all, so the drug just sits in their system, causing nausea, drowsiness, or no relief at all. Then there’s CYP2C19, which handles proton pump inhibitors like pantoprazole. Poor metabolizers of this gene can end up with five to ten times more drug in their blood than normal. That’s why the FDA recommends lower doses for kids with this genetic profile-otherwise, they risk long-term side effects like bone loss or nutrient deficiencies.The Dangerous Link Between HLA Genes and Severe Reactions

Some side effects aren’t just uncomfortable-they’re life-threatening. And for those, your immune system’s genetic code plays the starring role. The HLA-B*15:02 allele is one of the most well-documented examples. If you carry this gene variant and take carbamazepine (used for epilepsy and bipolar disorder) or phenytoin, your risk of developing Stevens-Johnson Syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN) goes up by 100 to 150 times. These conditions cause your skin and mucous membranes to blister and peel off, like a severe burn. In some cases, they’re fatal. The good news? If you test negative for HLA-B*15:02, your risk drops to nearly zero. That’s why doctors in Southeast Asia, where this variant is common, are required to test patients before prescribing these drugs. The FDA added this warning to drug labels over a decade ago, and since then, cases of SJS/TEN from these medications have dropped sharply in tested populations. Another HLA variant, HLA-B*57:01, warns of a severe reaction to the HIV drug abacavir. Almost everyone who has this gene and takes abacavir will get a dangerous hypersensitivity reaction-fever, rash, trouble breathing. But here’s the twist: only 5 to 10% of people who test positive for HLA-B*57:01 actually react. That means the test is perfect at ruling out risk (negative predictive value near 100%), but not perfect at predicting who will react. Still, because the reaction is so deadly, testing is now standard before prescribing abacavir.

Heart Drugs and Hidden Genetic Risks

Heart medications are another area where genetics can silently put you at risk. Warfarin, a blood thinner used to prevent strokes, has a narrow safety window. Too little, and you clot. Too much, and you bleed. Your genes explain up to 40% of why people need such different doses. Two genes-VKORC1 and CYP2C9-control how your body handles warfarin. If you carry certain variants of these genes, you might need just half the usual dose. Without genetic testing, it can take weeks of trial and error to find your safe level, with dangerous bleeding risks along the way. Now, the FDA recommends genetic testing before starting warfarin, and many hospitals have protocols to use this data from day one. Even more concerning are cases of drug-induced long QT syndrome, a heart rhythm disorder that can lead to sudden death. About 5% of people who develop this from common drugs like antibiotics or antipsychotics actually have a hidden, inherited form of long QT syndrome. Mutations in genes like KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A make their hearts more sensitive to drug effects. These mutations often go undetected until a drug triggers a dangerous rhythm. Genetic testing after a reaction can save lives-not just for you, but for your blood relatives too.Why Genetic Testing Isn’t Everywhere Yet

You might think, “If this is so important, why don’t all doctors test for it?” The answer is messy. Even though the FDA lists 128 gene-drug pairs with clear clinical guidance, only about 10 to 15% of doctors routinely use genetic testing in practice. Why? First, many doctors haven’t been trained to interpret the results. A 2023 survey found that nearly 70% of physicians felt unprepared to use pharmacogenetic data. Second, the cost of testing-$250 to $500-isn’t always covered by insurance. Medicare, for example, only covers testing for 7 of the 128 FDA-recommended gene-drug pairs. Third, getting genetic results into electronic health records is a technical nightmare. Hospitals need special software to flag high-risk prescriptions based on genetic data. Only 37% of U.S. hospitals have this setup. The Mayo Clinic’s RIGHT Protocol, which tests patients upfront for 10 key genes, reduced hospitalizations from drug side effects by 23%. But it required hiring pharmacogenetics specialists and spending over $1 million to integrate the system.Who Benefits Most from Genetic Testing?

Not everyone needs to be tested. But some groups get the biggest bang for their buck:- People starting long-term treatments like antidepressants, anticonvulsants, or chemotherapy

- Patients who’ve had unexplained side effects from a drug before

- Those of Asian descent (higher chance of HLA-B*15:02)

- People with a family history of severe drug reactions

- Children and older adults, whose bodies handle drugs differently

The Future: More Testing, More Precision

The field is moving fast. The All of Us Research Program has already returned pharmacogenetic results to over 200,000 Americans, and 42% of them carry at least one actionable variant. New tools are emerging too-like polygenic risk scores that combine dozens of genes to predict side effect risk, not just one. A 2024 study showed a 15-gene score predicted statin-induced muscle pain with 82% accuracy, far better than looking at SLCO1B1 alone. By 2030, experts predict 40% of prescription drugs will require genetic testing before use. The FDA is pushing for standardized rules, and Europe and Japan are already ahead of the U.S. in mandatory testing. But big gaps remain: less than 5% of genetic studies include enough people of African ancestry, even though they carry more genetic diversity and higher rates of certain variants. The bottom line? Your genes aren’t just about your eye color or height-they’re quietly shaping how your body handles every pill you take. If you’ve ever had a bad reaction to a medication, or if you’re starting a new long-term treatment, asking your doctor about pharmacogenetic testing might not just save you from discomfort-it could save your life.Can genetic testing prevent all drug side effects?

No, genetic testing can’t prevent all side effects. It’s most useful for predicting reactions tied to specific gene variants-like those affecting drug metabolism (CYP enzymes) or immune responses (HLA genes). But many side effects come from non-genetic factors: age, liver or kidney function, other medications, or lifestyle. Genetic testing reduces risk, not eliminates it.

Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance?

It depends. Some private insurers cover testing for specific high-risk drugs like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain cancer therapies. Medicare covers only 7 out of 128 FDA-recommended gene-drug pairs as of 2024. Most direct-to-consumer tests (like 23andMe) aren’t covered and don’t provide clinical-grade results. Always check with your provider and ask if the test is ordered by a doctor.

Do I need to be tested before every new medication?

No. Once you’ve had a comprehensive pharmacogenetic test, the results apply for life-your genes don’t change. You don’t need to be retested for every new drug. The key is making sure your results are stored in your medical record and accessible to any doctor prescribing you medication.

What if I get a false positive on a genetic test?

False positives are rare but possible. For example, some HLA-B*15:02 tests in Asian populations can give misleading results due to testing methods or genetic complexity. If a result seems inconsistent with your medical history, ask for confirmation with a different lab or expert review. Some variants, especially in CYP2D6, require specialized analysis because of gene duplications or deletions that standard tests miss.

Can I get tested without a doctor’s order?

Yes, companies like 23andMe and Color Genomics offer pharmacogenetic reports as part of their health services. But be careful: these tests aren’t always validated for clinical use, and they may not cover all high-risk gene-drug pairs. A doctor or pharmacist can help interpret the results in context with your health history. Never stop or change a medication based on a direct-to-consumer test alone.

Medications

Medications

Siobhan K.

December 20, 2025 AT 12:22Let’s be real-this isn’t science fiction anymore. I’ve seen patients on warfarin bleed out because their CYP2C9 variant wasn’t checked. It’s not about being paranoid; it’s about being competent. The fact that this isn’t standard care is a systemic failure, not a technical one.

Doctors aren’t lazy-they’re drowning in paperwork and underpaid. But when your life depends on a gene you can’t see, that’s not acceptable.

We need mandatory training, not optional modules. And insurance? They’ll pay for a CT scan that shows nothing, but balk at a $300 test that prevents a stroke or a skin graft.

It’s not about cost. It’s about who they value.

And no, I’m not mad. I’m just tired.

Sarah Williams

December 20, 2025 AT 19:30This is why I always ask for genetic testing now. My mom had a bad reaction to an antidepressant-nobody knew why. Turns out she’s a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. We found out after she spent 6 months in therapy. Don’t wait for your body to scream. Ask upfront.

Brian Furnell

December 21, 2025 AT 14:04Exemplary synthesis of pharmacogenomic principles-particularly the delineation between metabolic phenotypes (ultrarapid vs. poor metabolizers) and HLA-mediated immune hypersensitivity. The CYP2D6 polymorphism’s impact on codeine bioactivation is a textbook case of pharmacokinetic variability with life-or-death consequences.

Moreover, the VKORC1/CYP2C9 interaction in warfarin dosing exemplifies the clinical utility of genotype-guided anticoagulation. The FDA’s 128-gene-drug list is underutilized due to infrastructural inertia, not scientific uncertainty.

Polygenic risk scores, however, represent the next frontier: integrating epistatic interactions, regulatory SNPs, and non-coding variants into predictive algorithms. The 15-gene statin myopathy model (2024) is a landmark-far superior to SLCO1B1 alone.

Still, the lack of diversity in genomic databases remains a critical flaw. African populations harbor greater allelic heterogeneity, yet comprise <5% of GWAS cohorts. This is not just inequitable-it’s dangerous.

Peggy Adams

December 22, 2025 AT 14:43So you’re telling me Big Pharma doesn’t want us to know our genes because then we’d know which drugs are poison for us? And they’d lose money? Yeah, right. That’s why they still push the same pills on everyone. They don’t care if you die-they care if you keep buying.

They don’t test because they don’t want to know. Simple as that.

Jason Silva

December 23, 2025 AT 23:09Genetic testing? Nah. That’s just the government’s way to track you. 🤫

They’re putting microchips in the blood tests. I read it on a forum. Also, the FDA is owned by Pfizer. And the HLA thing? Totally fake. Your body’s just weak. Eat more kale. 💪🌱

Also, I took 3 Advil and got a rash. So yeah. Genes. Totally real. 😎

Swapneel Mehta

December 24, 2025 AT 16:00This is actually really helpful. I didn’t know my genes could affect how I react to medicine. I’ve always thought it was just bad luck when I got sick from a pill. Now I’ll ask my doctor next time I’m prescribed something new. Thanks for sharing.

Meina Taiwo

December 25, 2025 AT 15:40As a pharmacist in Lagos, I’ve seen this firsthand. A patient on carbamazepine developed SJS-turned out she was HLA-B*15:02 positive. No test was done. We lost her.

Testing isn’t expensive here. The real barrier? Awareness. We need community education, not just hospital protocols.

Also, African genomes are underrepresented in databases. That’s why our patients get misclassified. We need more local research.

Cara C

December 26, 2025 AT 20:07Thank you for writing this. I’m so glad someone’s talking about this. My daughter had a bad reaction to an antibiotic at age 5-we never knew why. If this had been around back then… I don’t know. Maybe she’d have avoided the hospital stay. Please, if you’re reading this-ask your doctor. Even if they say no, ask again.

Christina Weber

December 27, 2025 AT 00:59Incorrect usage of ‘allele’ in the HLA-B*15:02 context. It is a haplotype, not a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). Additionally, the FDA’s guidance is not ‘recommendation’-it is a boxed warning under 21 CFR 201.57. You also mischaracterized the predictive value of HLA-B*57:01 testing; it is not ‘near 100%’ for negative predictive value-it is 100% for ruling out abacavir hypersensitivity, per the FDA label. Grammar matters. Accuracy matters. This article deserves better editing.

Stacey Smith

December 27, 2025 AT 10:50So we’re supposed to trust some gene test from a lab instead of our doctor? In America, we don’t need this. We’ve got the best doctors in the world. This is just Europe’s overregulation creeping in. We don’t need more bureaucracy. We need less government telling us what to do.

Southern NH Pagan Pride

December 27, 2025 AT 19:22They’re using your DNA to build a database for the New World Order. You think they care about your health? They care about controlling you. That’s why they push these tests-so they can tag you as ‘high-risk’ and deny you insurance later. And don’t get me started on the mRNA link. 🕵️♀️

Also, my cousin got a rash from ibuprofen. He’s a witch. That’s why. Genes? Nah. It’s the chemtrails.

Orlando Marquez Jr

December 28, 2025 AT 17:32The pharmacogenomic paradigm shift represents a significant advancement in precision medicine. However, the current implementation challenges-including physician education, reimbursement policy, and EHR integration-remain formidable. The Mayo Clinic’s RIGHT Protocol demonstrates the feasibility of institutional-scale implementation, yet scalability across diverse healthcare systems requires coordinated federal policy, standardized data formats, and cross-sector collaboration. The ethical imperative is clear; the logistical path remains complex.

mukesh matav

December 30, 2025 AT 02:59My uncle died from a drug reaction. No one knew why. I never thought it could be in our genes. Now I’m getting tested. Just in case.

Theo Newbold

December 31, 2025 AT 08:15Let me break this down for the people who think this is science: 90% of these ‘actionable variants’ are statistical noise. The studies are underpowered. The clinical utility is overstated. And the labs? They’re selling tests like lottery tickets. You think your CYP2D6 status means anything when your liver is fried from alcohol and Tylenol? Wake up. It’s not genetics. It’s lifestyle. And the whole industry is a money grab.

Stop believing in magic DNA.