When a pharmacist fills a prescription, they’re not just handing out pills-they’re making a critical decision that affects safety, cost, and patient trust. The difference between a brand-name drug and its generic version might seem simple: one costs more, the other less. But behind that choice lies a complex system of codes, regulations, and software rules that must work perfectly to avoid errors. In pharmacy systems today, generic vs brand identification isn’t just about saving money-it’s about preventing harm.

How Pharmacy Systems Tell Generic from Brand

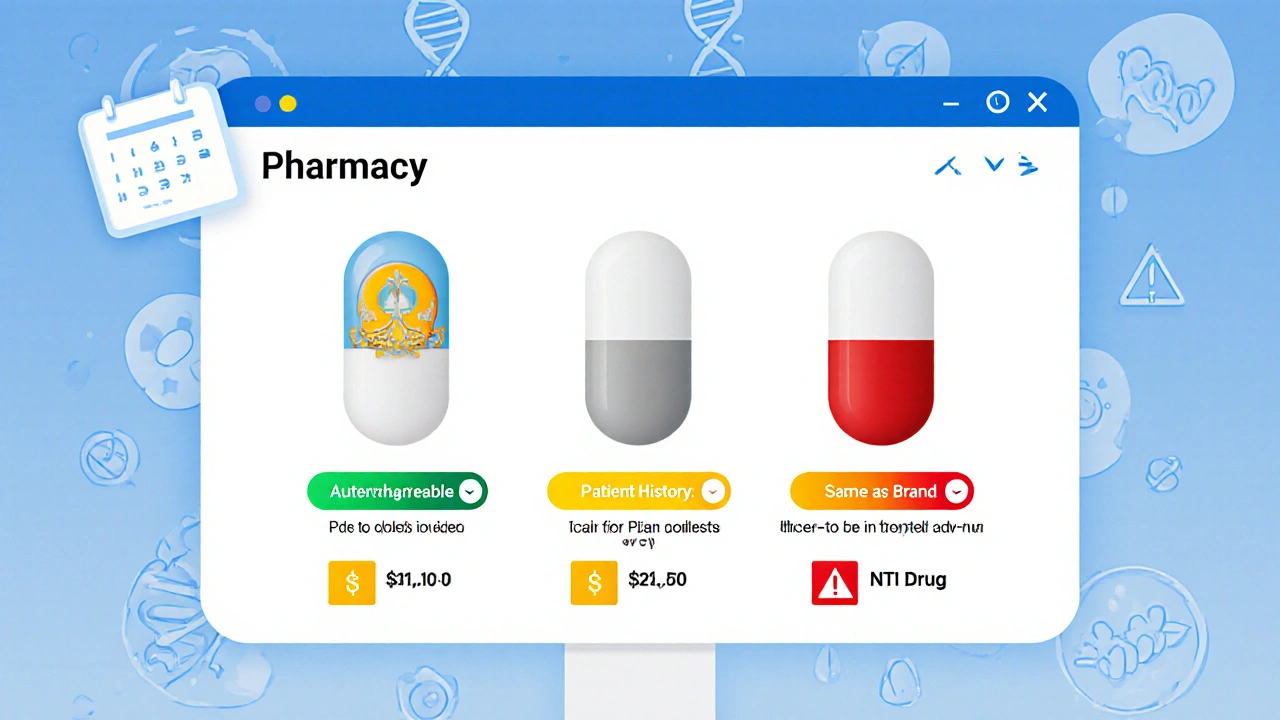

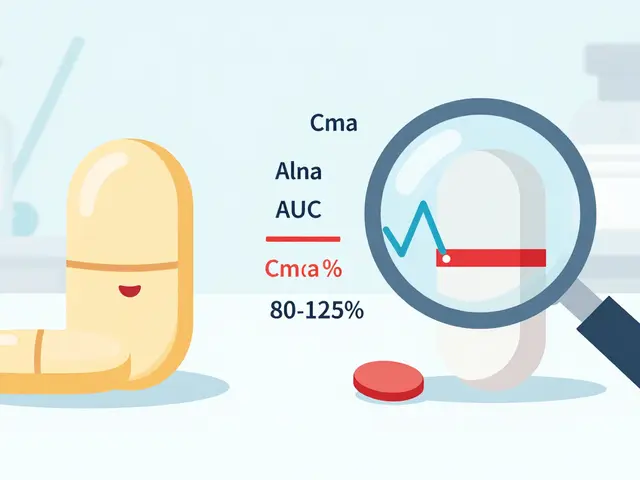

Every medication in the U.S. has a unique identifier called the National Drug Code (NDC). This 10- or 11-digit number acts like a fingerprint for each drug product. But here’s the catch: the same active ingredient can have dozens of NDCs. One might be the brand-name version made by Pfizer. Another could be a generic made by Teva. A third might be an authorized generic-exactly the same drug, just sold under a different label. Pharmacy systems rely on the FDA’s Orange Book to sort this out. The Orange Book doesn’t just list drugs-it assigns each one a Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) code. If a drug has an ‘A’ code like AB or AO, it’s considered interchangeable with the brand-name version. That means a pharmacist can legally substitute it without needing a new prescription. But if the code is ‘B’, it’s not considered equivalent. That’s a red flag. Systems like Epic, Cerner, and Rx30 pull this data directly from the FDA’s monthly updates. But not all systems are equal. Some older platforms still use outdated databases. One pharmacist in Ohio reported her system flagged a generic lisinopril as ‘not equivalent’-even though it was approved two years ago. The issue? The database hadn’t synced with the latest Orange Book version. That’s not just inconvenient-it’s dangerous.Authorized Generics and Branded Generics: The Hidden Confusion

Not all generics are created equal in appearance. Authorized generics are the real deal: identical to the brand in every way, down to the inactive ingredients. They’re made by the same company that produces the brand, just sold under a generic label to compete on price. For example, the brand-name drug Prilosec and its authorized generic omeprazole are chemically the same. But pharmacy systems don’t always make that clear. Then there are branded generics. These are generics that got FDA approval through the ANDA process but were given catchy names like Errin, Jolivette, or Sprintec. To a patient, these look like brand-name drugs. To a pharmacist, they’re still generics. But if the system doesn’t clearly label them, a patient might think they’re being charged extra for a brand when they’re not. A 2022 survey found 78% of pharmacists struggled to distinguish between branded generics and true brands when filling birth control prescriptions. The real problem? Patients don’t know the difference. A Kaiser Permanente study showed that when patients saw a visual comparison on their portal-showing side-by-side images of brand and generic with matching active ingredients-requests to stick with the brand dropped by 37%.Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs: When Substitution Can Be Risky

Some drugs have zero room for error. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. A tiny change in blood levels can mean the difference between control and crisis. Warfarin, phenytoin, levothyroxine, and lithium fall into this category. Here’s where pharmacy systems should be smart. Systems like Epic’s Beacon Oncology have built-in rules that block automatic substitution for NTI drugs. But not all systems do. In 2021, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices documented 147 adverse events linked to inappropriate generic substitution of warfarin. In one case, a patient’s INR spiked after switching to a different generic. The pharmacy system didn’t flag it because both versions had an ‘AB’ code. But the patient had a history of sensitivity. The system didn’t know that. That’s why best practice isn’t just about code matching-it’s about context. A patient who’s been stable on a specific brand of levothyroxine for five years? Their system should prompt the pharmacist: “Patient has been on this formulation since 2019. Consider holding substitution.”

State Laws and the Patchwork of Rules

The federal government sets the baseline, but states run the show when it comes to substitution. Forty-nine states allow pharmacists to substitute generics without prescriber approval-so long as the TE code says it’s safe. But how they document it? That’s where things get messy. California requires pharmacists to record why a brand was kept instead of a generic. Texas doesn’t require any documentation at all. Florida requires a note in the patient’s file if the patient refuses a generic. One pharmacy chain’s system in Florida auto-generated a note for every substitution. In Texas, it didn’t. That created compliance nightmares during audits. And then there’s the NDC directory. It changes about 3,500 times a month. A new generic gets approved. An old one gets discontinued. A manufacturer changes its packaging. If your system doesn’t update daily, you’re working with outdated data. That’s why top-performing pharmacies use APIs from the FDA’s Orange Book and DailyMed-not static downloads.What Works: Real-World Best Practices

Kaiser Permanente doesn’t just use tech-they use culture. Their system defaults to generics. But it doesn’t force it. If a prescriber writes “Dispense as Written,” the system flags it. If a patient has had a bad reaction to a previous generic, the system remembers. And every time a generic is dispensed, the patient gets a simple handout: “This is the same medicine, just cheaper.” Humana’s system takes it further. It doesn’t just suggest generics-it suggests the *best* generic. If three generics are available, it picks the one with the lowest cost and highest patient satisfaction score based on historical data. Then it notifies the prescriber. Result? A 22% increase in generic use-with no rise in adverse events. Even small pharmacies can adopt best practices. Start with three steps:- Make sure your system pulls live data from the FDA Orange Book API-not monthly updates.

- Set defaults to generic names in your dispensing screen, but require a click to override.

- Train staff on the difference between authorized generics and branded generics. Use visual aids. Show them the NDC lookup tool.

Patient Education Is the Missing Link

Here’s the hard truth: 68% of patients don’t know that generics have the same active ingredients as brand-name drugs. That’s not their fault. It’s the system’s failure. A 2022 Consumer Reports survey found that when patients were told upfront why a generic was being dispensed, 89% were satisfied. When they weren’t told, satisfaction dropped to 63%. The difference? Clarity. Pharmacists who hand out a simple one-page sheet-showing the brand name, generic name, active ingredient, and a checkmark saying “Same medicine, lower cost”-see fewer calls, fewer complaints, and more trust.The Future: AI, Genomics, and Real-Time Alerts

The next wave of pharmacy systems won’t just identify drugs-they’ll predict problems. A 2023 study in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association tested an AI tool that analyzed 1.2 million prescriptions. It flagged potential equivalence issues with 87.3% accuracy, especially for NTI drugs. Soon, systems might integrate pharmacogenomic data. If a patient has a gene variant that affects how they metabolize levothyroxine, the system could auto-suggest they stay on a specific brand-even if a generic is cheaper. The FDA’s 2023 initiative to make the Orange Book machine-readable will help. Real-time updates mean fewer delays. Fewer delays mean fewer errors.Final Takeaway: It’s Not About Brand or Generic-It’s About Accuracy

The goal isn’t to push generics. The goal is to make sure the right drug gets to the right patient at the right time. Whether it’s brand, generic, authorized generic, or branded generic-the system must know the difference. And the pharmacist must understand it too. The best pharmacy systems don’t just automate. They inform. They alert. They educate. They remember. And above all, they don’t assume.Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also prove bioequivalence-meaning they deliver the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream at the same rate. Studies show no meaningful difference in effectiveness for most drugs. The only exceptions are rare cases involving narrow therapeutic index drugs or individual patient sensitivities to inactive ingredients.

Why do some pharmacists hesitate to substitute generics?

Some pharmacists worry about patient reactions, especially with drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin, where small changes in blood levels can matter. Others are confused by branded generics that look like brand-name drugs. System errors-like outdated NDC data or missing TE codes-also cause hesitation. Training and clear protocols help reduce these concerns.

What’s the difference between an authorized generic and a regular generic?

An authorized generic is made by the same company that produces the brand-name drug, using the same ingredients and manufacturing process. It’s sold under a generic label to compete on price. A regular generic is made by a different company and may have different inactive ingredients. Both are FDA-approved, but authorized generics are chemically identical to the brand.

Can pharmacy systems automatically switch me to a generic without my doctor’s approval?

In 49 U.S. states, yes-if the drug has a therapeutic equivalence code of ‘A’ and the prescription doesn’t say “Dispense as Written.” The pharmacist must follow state laws, which vary. Some states require documentation; others don’t. Always ask if a substitution was made, and check your receipt.

Why do some generics look different from the brand?

By law, generics don’t have to look the same as the brand. Color, shape, and inactive ingredients can differ. This is intentional to avoid trademark infringement. But the active ingredient must be identical. If you notice a change in how a medication works after switching, tell your pharmacist-it could be an excipient issue, not the active drug.

How often do pharmacy systems update their drug databases?

Top systems update daily using live APIs from the FDA’s Orange Book and DailyMed. But many older or low-cost systems only update monthly or quarterly. That lag can cause errors-like missing a newly approved generic or failing to flag a discontinued drug. Always ask your pharmacy if they use real-time updates.

Do insurance companies push pharmacists to use generics?

Yes. Most insurance plans require patients to try generics first before covering the brand-name version. This is called step therapy. Pharmacists are often required to substitute unless the prescriber specifically says “Dispense as Written.” But this doesn’t mean they can override safety protocols-like blocking substitution for NTI drugs.

What should I do if I think a generic isn’t working for me?

Don’t stop taking it. Contact your pharmacist first. They can check if you switched to a different generic or if there’s a change in inactive ingredients. If you’re still having issues, ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” on the prescription. You can also request the specific brand or generic version you’ve been using successfully.

Medications

Medications

Shante Ajadeen

November 12, 2025 AT 20:50Just wanted to say this post nailed it. I work in a small pharmacy and seeing patients actually understand that generics are the same medicine? Game changer. We started handing out those one-pagers last month. Calls dropped, trust went up. Simple stuff, but nobody was doing it.

Danae Miley

November 13, 2025 AT 03:31Let’s be real-pharmacy systems are still running on dinosaur software. I’ve seen a Cerner install from 2017 flag lisinopril as ‘B’ code because the FDA update hadn’t been manually imported since 2020. This isn’t a tech problem-it’s a budget problem. Hospitals won’t pay for APIs, so patients pay with their health.

Andrew Forthmuller

November 13, 2025 AT 20:27My cousin switched generics for warfarin and ended up in the ER. System didn’t flag it. Neither did the pharmacist. Don’t assume ‘AB’ means safe.

Benjamin Stöffler

November 14, 2025 AT 14:41One must ask: is the real issue not the NDC, not the TE code, nor even the pharmacist’s training-but the philosophical assumption that ‘equivalence’ is a binary state? In pharmacology, as in all things biological, variation is inherent. The FDA’s ‘A’ code is a statistical approximation, not a metaphysical truth. To treat generics as interchangeable without context is to confuse mathematical precision with biological reality. We are not machines; our bodies are not APIs. And yet, we outsource life-or-death decisions to a database that updates once a month.

When a patient has been on the same levothyroxine brand since 2019, and their TSH is stable at 2.1, why does a system-designed to optimize cost-override the lived experience of the human body? The algorithm sees cost savings. The patient sees anxiety, tremors, fatigue. The system is not wrong-it is incomplete. And incompleteness, in medicine, is not inefficiency. It is negligence.

AI might one day integrate pharmacogenomics-but until then, we are trusting the silent, unfeeling logic of software to interpret the silent, complex poetry of human physiology. That is not progress. That is surrender.

Elizabeth Buján

November 15, 2025 AT 23:02OMG I just realized my pharmacy switched my generic for my anxiety med and I didn’t even notice until I googled it. I thought I was going crazy for like 3 weeks. Then I saw the pill looked different. I asked my pharmacist and they said ‘it’s the same thing’ but I didn’t feel it. I asked for my old one back and they gave it to me. Now I always check the pill. Don’t trust the label. Trust your body.

vanessa k

November 17, 2025 AT 12:44My grandma takes levothyroxine and she swears the brand version works better. I used to think she was just being stubborn. But after reading this, I looked up her NDC and found out she’s been on the same generic since 2018. The manufacturer changed the filler in 2021. She never told anyone. Now I’m printing out those info sheets for her. She deserves to know what’s in her body.

dace yates

November 18, 2025 AT 03:47So… if an authorized generic is chemically identical to the brand, why does it cost less? And why isn’t it labeled as such on the bottle? I’ve seen patients refuse it because they think it’s ‘fake’.

Nicole M

November 19, 2025 AT 05:40My pharmacy uses a free system that updates every 3 months. I asked them why and they said ‘it’s cheaper than the API’. I told them I’d rather pay $10 more a month than risk a bad reaction. They switched to the paid version last week. I’m not mad. I’m just glad I spoke up.

Arpita Shukla

November 20, 2025 AT 20:45Why are we even debating this? The FDA doesn’t require generics to match inactive ingredients. That’s why some people get rashes, stomach issues, or headaches. It’s not placebo. It’s excipients. Stop pretending generics are 100% identical. They’re not. And patients deserve to know what’s in the pill besides the active ingredient.

Charles Lewis

November 22, 2025 AT 12:08It is imperative that we recognize the structural deficiencies within our current pharmaceutical information infrastructure. The reliance on static, monthly database updates is not merely an operational oversight-it is a systemic failure of due diligence in patient safety. When a pharmacy system fails to synchronize with the FDA’s Orange Book on a daily basis, it effectively renders its clinical decision support tools obsolete. This is not a question of cost efficiency; it is a moral imperative. The patient who receives a substituted medication based on outdated data is not merely inconvenienced-they are put at risk. The integration of real-time APIs, while financially burdensome for smaller institutions, must be prioritized as a non-negotiable standard of care. Furthermore, the absence of mandatory patient education materials at the point of dispensing represents a profound failure of communication ethics. We do not expect patients to navigate complex legal codes or pharmacological taxonomies; we are obligated to simplify, clarify, and empower. The Kaiser Permanente model is not an innovation-it is a baseline expectation.

Mark Rutkowski

November 24, 2025 AT 01:37There’s a quiet revolution happening in pharmacies right now, and nobody’s talking about it. It’s not about tech or cost. It’s about dignity. When a pharmacist hands you a pill and says, ‘This is the same medicine, just cheaper,’ they’re not just filling a prescription-they’re restoring trust. For years, we’ve treated patients like accounting entries. Now, we’re starting to treat them like people. That’s the real breakthrough. The system can flag NTI drugs. It can suggest the cheapest generic. But only a human can say, ‘I know this one worked for you before.’ That’s the magic. Not the API. Not the code. The care.

Renee Ruth

November 25, 2025 AT 01:12Let’s not sugarcoat this: pharmacy systems are a disaster. I’ve seen patients get the wrong drug because the system confused two NDCs that differed by one digit. One pharmacist got fired for it. The company? They just upgraded to a new system that still doesn’t update in real time. This isn’t incompetence-it’s negligence wrapped in a corporate policy. Someone’s going to die because a database wasn’t paid for. And when they do, the board will tweet ‘our hearts go out to the family’ while keeping the same budget.

manish kumar

November 26, 2025 AT 07:05As a pharmacist in India, I see this every day. We don’t even have NDCs here. We rely on brand names and color codes. But generics are everywhere-some good, some terrible. We train our staff to check the manufacturer, the batch number, even the smell sometimes. It’s not ideal. But when you don’t have a digital system, you learn to trust your eyes and your experience. This post made me realize we’re not so different after all. The struggle is global. The solution? Education. Always education.