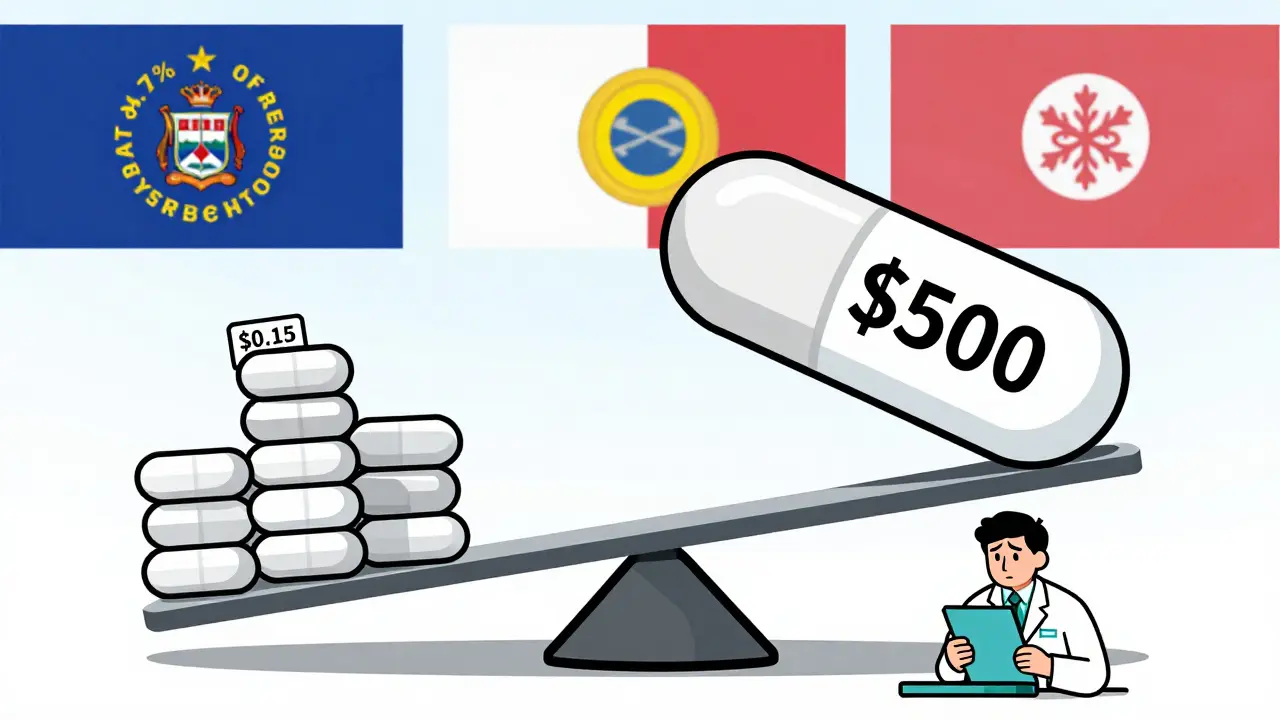

Medicaid spends billions on prescription drugs every year - but most of that money isn’t going to brand-name pills. In fact, generic drugs make up 84.7% of all Medicaid prescriptions, yet they account for just 15.9% of total drug spending. That’s the power of generics. But even with these massive savings, states are still scrambling to control costs. Why? Because when a single generic drug suddenly jumps from $5 to $500 overnight, it breaks budgets. And it’s happening more often.

How the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program Works (And Why It’s Not Enough)

The federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) has been the backbone of generic drug pricing since 1990. Under this system, drug manufacturers must give Medicaid a rebate for every pill they sell. For generics, that rebate is 13% of the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP), or the difference between AMP and the best price offered to other buyers - whichever is higher. Sounds fair, right?

But here’s the catch: the rebate formula doesn’t change when a drug’s price spikes. If a manufacturer raises the price of a 50-year-old generic antibiotic from $10 to $500, the rebate still only kicks in at 13% of that new, inflated price. That means Medicaid ends up paying $435 more per prescription - and the rebate only covers $65 of it. The rest? Taxpayers foot the bill.

States can’t negotiate extra rebates on generics like they can with brand-name drugs. That’s a federal rule. So while states have some control over how they pay pharmacies, they’re stuck with a broken system when manufacturers play games with pricing.

Maximum Allowable Cost Lists: The Most Common State Tool

Forty-two states now use Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists to cap how much they’ll pay for a generic drug. Think of it like a price ceiling. If a pharmacy tries to bill Medicaid for a generic ibuprofen at $12, but the state’s MAC is $3, Medicaid only pays $3. The pharmacy eats the difference - or switches to a cheaper supplier.

Thirty-one states update these lists quarterly or more often. That’s good - because generic prices can swing wildly. But 68% of states update them monthly or less. That’s a problem. When a drug drops to $1.50 but the MAC hasn’t been updated in three months, pharmacies can’t get paid fairly. Patients might even be denied the drug because the pharmacy can’t afford to stock it at the old price.

Independent pharmacies report that 74% have faced delayed payments or claim rejections because their MAC lists are out of sync with real market prices. That’s not just a billing issue - it’s a access issue. People who rely on Medicaid can’t get their meds because the system is too slow to react.

Mandatory Generic Substitution: A Simple Win

Forty-nine states require pharmacists to substitute a generic drug when it’s available - unless the doctor says no. This isn’t new. It’s been standard practice for years. But it’s still one of the most effective cost controls out there.

When a doctor prescribes Lipitor (a brand-name cholesterol drug), the pharmacist can legally give the patient atorvastatin instead - the generic version - at a fraction of the cost. And patients rarely notice the difference. Studies show that 90% of patients on generic substitutions report the same effectiveness and side effects.

But some states are going further. Twenty-eight states now use Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs) that don’t just require substitution - they actively steer prescribers toward the cheapest generic in a class. If there are three equally effective generic blood pressure pills, the state will only cover the one that costs $2 instead of $8. Doctors get alerts in their electronic systems. Pharmacies get incentives. It’s not forcing anyone’s hand - it’s guiding smarter choices.

Cracking Down on Price Gouging

Some generic drug price hikes aren’t just high - they’re illegal. In 2020, Maryland became the first state to pass a law that bans manufacturers from raising prices on generic drugs without new clinical data. If a company hikes the price of a drug that’s been on the market for 20 years - with no new research or improvements - and the increase is deemed “unjustified,” they can be fined.

Since then, states like California, Colorado, and Minnesota have followed suit. Minnesota even tied its generic drug price caps to the Inflation Reduction Act’s pricing benchmarks. These laws don’t target every price change. They target the ones that make no sense: a 500% jump on a drug that hasn’t changed since the 1980s.

It’s not a silver bullet. Manufacturers still find loopholes - like releasing a “new” version with a slightly different pill shape to reset pricing. But it’s a start. And it sends a message: you can’t just exploit a broken system.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Hidden Middlemen

Thirty-three states hire Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) like OptumRx, Magellan, or Conduent to handle their Medicaid pharmacy benefits. These companies act as intermediaries between states, pharmacies, and drugmakers. They negotiate rebates, set MAC lists, and process claims.

But here’s the problem: PBMs don’t always pass savings along. They keep a cut - sometimes as much as 20% - of what they save. And they often don’t disclose what they actually pay for drugs. In 2024, 27 states started requiring PBMs to report their true acquisition costs. Nineteen of them now require full transparency: what the PBM paid, what they billed the state, and how much they kept.

That’s huge. Because without knowing what’s really happening behind the scenes, states can’t fix the system. If a PBM says a generic drug costs $4 to buy but bills Medicaid $12, and keeps $6 for itself - that’s not savings. That’s profit at the patient’s expense.

Supply Chain Woes: When Generics Disappear

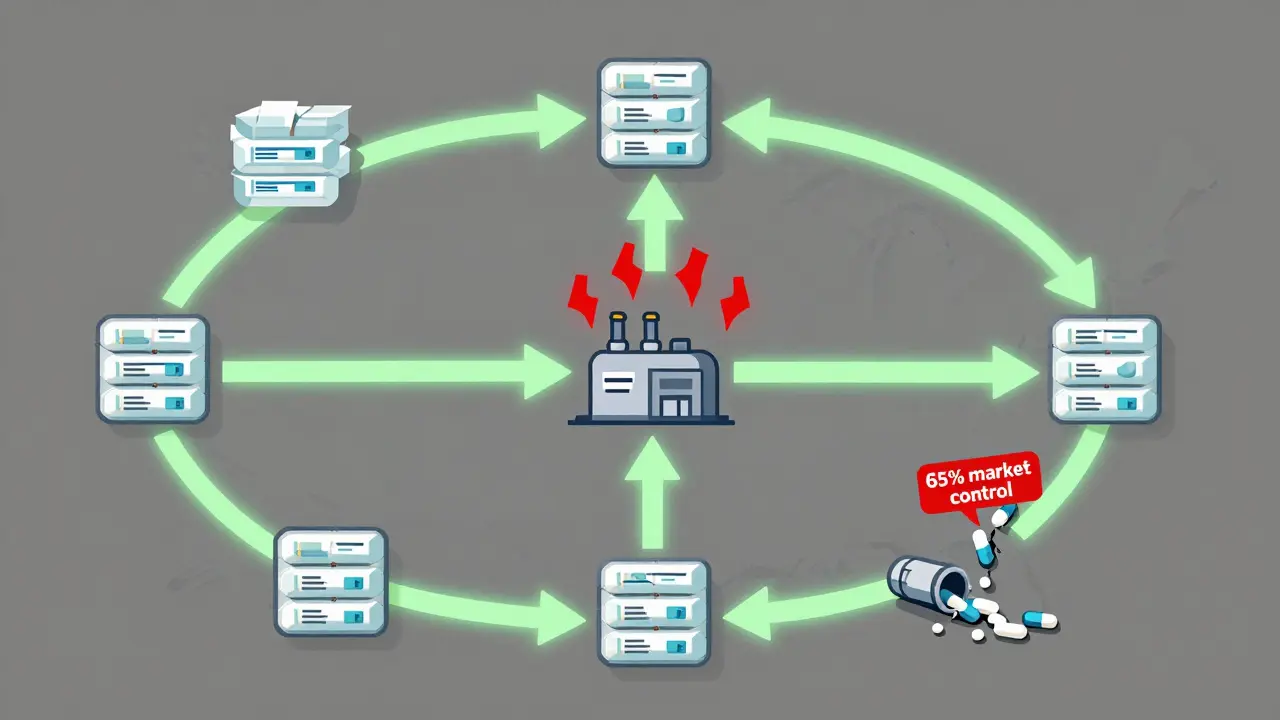

There’s another quiet crisis: shortages. In 2023, 23 states reported shortages of critical generic drugs - antibiotics, insulin, seizure meds, heart drugs. The average shortage lasted 147 days. Why? Because generic drug manufacturing is concentrated. Three companies now control 65% of the generic injectables market. If one factory has a quality issue - boom - the whole country runs out.

Twelve states introduced legislation in 2024 to build strategic stockpiles of high-risk generics. Oregon and Washington launched a multi-state purchasing pool to buy 47 high-volume generics in bulk, locking in lower prices and ensuring backup supply. Texas is carving out gene therapies from its main Medicaid program - a move that could set a precedent for managing other high-cost generics.

It’s not just about price anymore. It’s about reliability. If a patient can’t get their generic blood pressure pill because the only manufacturer had a shutdown, they might end up in the ER - costing the system way more than the drug ever did.

What’s Next? The Future of Generic Drug Pricing

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that state-level actions could cut generic drug spending by 5-8% annually. That’s $3.8 billion saved by 2027. But there’s a warning: if states go too far - if they cap prices so low that manufacturers can’t profit - supply could dry up. That’s why the CBO also warns that overly aggressive price controls could increase overall Medicaid spending by 2.3% as patients are forced onto more expensive brand-name drugs.

Meanwhile, the FDA and CMS are watching closely. In March 2025, CMS dropped its own federal drug pricing model - shifting all focus to state efforts. That means states are now the lab for the nation’s drug pricing future.

States are also bracing for GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy. These aren’t generics - yet. But if federal rules force Medicaid to cover them for obesity treatment, KFF estimates it could cost state programs $1.2 billion extra per year. That’s why states are already building prior authorization rules, step therapy requirements, and utilization limits. They’re preparing for the next wave.

The bottom line? Generic drugs are the unsung heroes of Medicaid cost control. But they’re under pressure - from price gouging, supply chain fragility, and middlemen who don’t always act in patients’ best interests. The states that are winning are the ones combining smart policy with real-time data, transparency, and a focus on access - not just savings.

What Works - And What Doesn’t

Here’s what’s proven effective:

- Updating MAC lists monthly or more often

- Requiring PBM transparency on acquisition costs

- Enforcing anti-price-gouging laws on old generics

- Using preferred drug lists to steer toward the lowest-cost option

- Building state-level stockpiles for critical shortages

Here’s what backfires:

- Capping prices so low that pharmacies stop stocking the drug

- Not updating MAC lists fast enough, creating access gaps

- Ignoring PBM profits and assuming savings are being passed on

- Targeting only generics while ignoring specialty drug spikes

States aren’t trying to eliminate profit. They’re trying to eliminate exploitation. And that’s a line most Americans - patients, pharmacists, and policymakers - can agree on.

Do all states have the same generic drug policies?

No. While all 50 states and DC cover prescription drugs under Medicaid, how they control costs varies widely. Some states use strict Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists, while others focus on transparency with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). A few, like Maryland and California, have passed laws against price gouging on generics. Others rely on preferred drug lists or therapeutic substitution rules. There’s no national standard - each state designs its own approach based on budget, political climate, and drug usage patterns.

Why don’t Medicaid rebates prevent generic drug price spikes?

Medicaid’s rebate formula for generics is fixed at 13% of the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). If a drug’s price jumps from $10 to $500, the rebate only covers 13% of that new price - meaning Medicaid still pays $435 more per prescription. The system doesn’t adjust for inflation or market manipulation. Unlike brand-name drugs, states can’t negotiate extra rebates on generics. So even though the rebate exists, it doesn’t stop manufacturers from raising prices - it just reduces the loss slightly.

What is a Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) list?

A Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) list is a state-set price cap for generic drugs. If a pharmacy tries to bill Medicaid more than the MAC amount for a generic drug, Medicaid only pays the MAC price. The pharmacy must absorb the difference or switch to a cheaper supplier. MAC lists help control costs, but if they’re not updated often enough, pharmacies can lose money - leading to drug shortages or delayed payments.

Are generic drugs as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as their brand-name counterparts. They must also meet the same strict manufacturing standards. Studies show that 90% of patients on generic drugs report the same effectiveness and side effects as with brand-name versions. The only differences are usually in inactive ingredients like fillers or pill color - which don’t affect how the drug works.

Why are generic drug shortages happening more often?

Generic drug manufacturing is highly concentrated - three companies control 65% of the market for generic injectables. If one factory has a quality issue, regulatory delay, or shutdown, it can cause nationwide shortages. Low profit margins also mean manufacturers often don’t invest in backup production or supply chain resilience. When prices are capped too low, companies may stop making certain generics altogether because they’re not profitable. This creates a dangerous cycle: low prices → less production → shortages → higher prices → more instability.

How do Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) affect Medicaid drug costs?

PBMs act as middlemen between states, pharmacies, and drugmakers. They negotiate rebates, set payment rates, and process claims. But many don’t disclose how much they actually pay for drugs or how much they keep as profit. In 2024, 27 states started requiring PBMs to report their true acquisition costs. Nineteen states now require full transparency - meaning states can see if PBMs are keeping too much of the savings. Without this data, states can’t tell if they’re truly saving money or just paying higher fees.

Can states force manufacturers to lower generic drug prices?

Not directly - federal law limits state power to negotiate rebates on generics. But states can use indirect tools: anti-price-gouging laws (like Maryland’s), MAC lists, and requiring PBM transparency. Some states also use multi-state purchasing pools to buy generics in bulk and negotiate better prices collectively. While they can’t force a manufacturer to lower prices, they can make it unprofitable to overcharge - and that’s often enough to change behavior.

Medications

Medications