Why your body might react differently to a biosimilar than to the original biologic

You might think if a drug is called a "biosimilar," it’s just like a generic pill - same active ingredient, same effect, same risk. But that’s not true. Biosimilars aren’t copies of biologics like generics are of small-molecule drugs. They’re made from living cells, and even tiny changes in how those cells are grown, processed, or stabilized can change how your immune system sees them. That’s where immunogenicity comes in - the chance your body will spot the drug as foreign and attack it.

It’s not just about whether the drug works. It’s about whether your immune system starts making antibodies against it. These are called anti-drug antibodies, or ADAs. And when they form, they can make the drug less effective, cause new side effects, or even trigger dangerous reactions like anaphylaxis. That’s why immunogenicity isn’t a footnote in biosimilar development - it’s the biggest safety question left unanswered after approval.

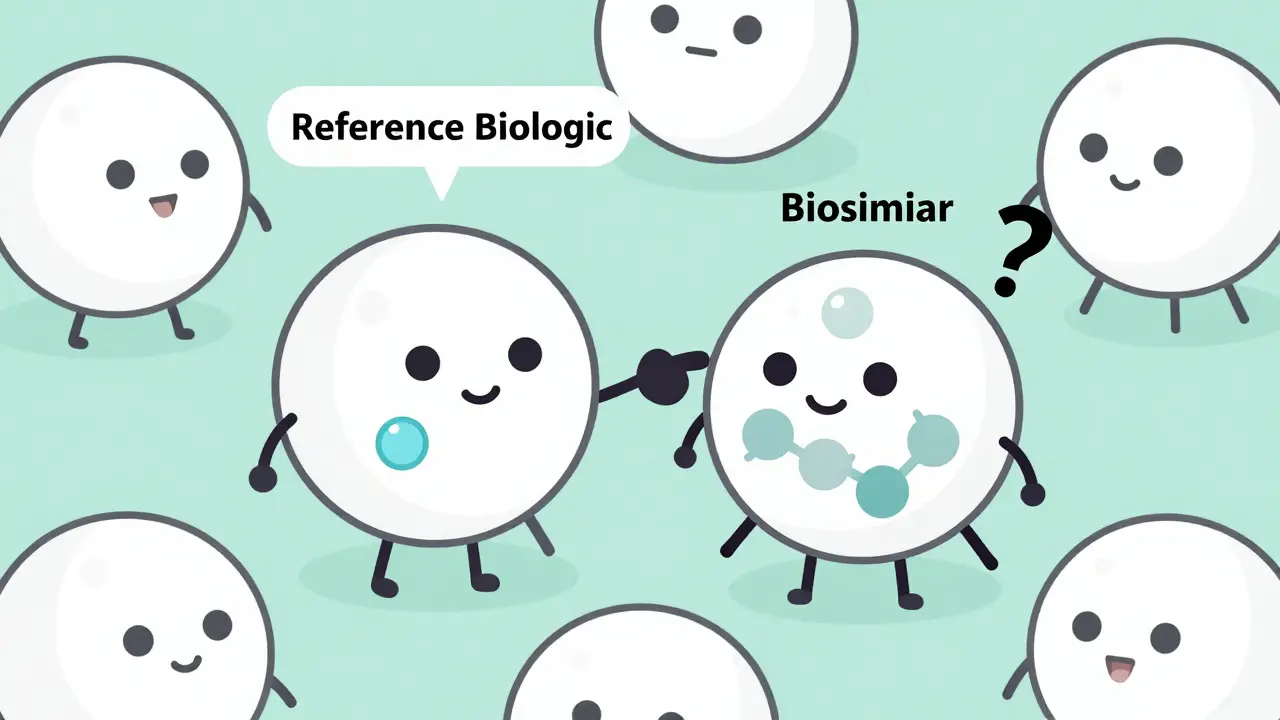

How biosimilars are different from generics

Think of a generic aspirin. It’s chemically identical to brand-name aspirin. Same molecule. Same atoms. Same shape. You can’t tell them apart under a microscope. Biosimilars? Not even close.

Biologics - like Humira, Enbrel, or Rituxan - are made from living cells. They’re proteins, sometimes hundreds of thousands of times bigger than a typical pill. And they come with a messy set of modifications: sugars attached (glycosylation), folded shapes, tiny fragments clipped off, or extra bits stuck on. These aren’t just decoration - they affect how the drug behaves in your body. Even a 1% difference in sugar patterns can change how your immune cells recognize it.

That’s why a biosimilar can be "highly similar" but not identical. The manufacturer uses a different cell line, different growth conditions, or a different purification process. The end product is close - but not a clone. And your immune system? It notices.

What triggers an immune response?

Your immune system doesn’t just attack viruses and bacteria. It’s always scanning for anything that looks "off." For biologics, that "off" signal can come from:

- Protein aggregates - clumps of molecules stuck together. Even 5% of these can triple your risk of developing ADAs.

- Host cell proteins - leftover bits from the manufacturing cells. If there’s more than 100 parts per million, ADA risk jumps by 87%.

- Wrong sugar attachments - like galactose-α-1,3-galactose, which triggered deadly allergic reactions with cetuximab.

- Stabilizers - polysorbate 80 vs. 20, for example. Sounds minor, but it can change how the protein unfolds and exposes new targets for antibodies.

And it’s not just the drug. Your body matters too. If you have rheumatoid arthritis, your immune system is already on high alert - you’re 2.3 times more likely to develop ADAs than a healthy person. If you’re taking methotrexate along with your biologic, that cuts ADA risk by 65%. Genetics play a role too - certain HLA gene variants can make you 4.7 times more likely to react.

How administration affects your risk

Where and how often you get the drug matters more than you’d think.

Injecting under the skin (subcutaneous) is way more likely to trigger an immune response than getting it through an IV. Why? Because the skin is packed with immune cells - dendritic cells that are experts at spotting foreign proteins. Studies show subcutaneous delivery increases immunogenicity risk by 30-50% compared to IV.

Frequency matters too. If you’re getting the drug every two weeks, your immune system has time to catch its breath. But if it’s intermittent - say, every 8 weeks - your immune system gets a fresh reminder each time. That’s like ringing a bell repeatedly. Eventually, your body starts salivating - or in this case, making antibodies.

And time? The longer you’re on the drug, the higher the chance your immune system breaks tolerance. Most ADAs show up after 6 months. That’s why short-term trials can miss the real risk.

Do real-world studies show real differences?

Here’s where things get messy.

In a 2021 study of 1,247 rheumatoid arthritis patients, the biosimilar CT-P13 (for infliximab) showed almost the same ADA rate as the original - 11.8% vs. 12.3%. No difference.

But the NOR-SWITCH trial, where patients switched from originator to biosimilar, saw a rise: 8.5% for the original, 11.2% for the biosimilar. Still, no drop in effectiveness.

Then there’s the Danish registry. For adalimumab, the original Humira had a 18.7% ADA rate. The biosimilar Amgevita? 23.4%. Statistically different. But patients still responded just as well to both.

On Reddit, patients report everything from zero difference to severe injection-site reactions after switching. One person wrote: "I got hives and swelling with the biosimilar - never happened with Humira." Another said: "Switched to biosimilar rituximab three years ago. No issues. Still working fine."

So what’s going on? The answer might be in the testing.

Why the tests don’t always tell the whole story

Regulators require biosimilars to be tested head-to-head with the original - same patients, same assay, same timing. But not all labs use the same tools.

Some use electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assays - super sensitive. They catch ADAs in 13.1% of patients. Others use older ELISA methods - they might only catch 5%. That’s not a real difference in the drug. That’s a difference in the test.

And neutralizing antibodies? Those are the scary ones. They don’t just bind to the drug - they block it from working. Testing for them requires cell-based assays, which are less precise (25-30% variation) but more biologically relevant. Many studies skip them because they’re expensive and messy.

Without identical methods, you can’t compare apples to apples. That’s why the EMA insists: "Comparative immunogenicity must use the same assay, same patient population, same timing." But not all trials follow that.

What does this mean for you?

If you’re on a biologic and your doctor suggests switching to a biosimilar, here’s what you should know:

- Most people switch without any issue. The majority of studies show no drop in effectiveness.

- But if you’ve had side effects before - especially allergic reactions or injection-site reactions - talk to your doctor. You might be more sensitive.

- If you’re on methotrexate, your risk is lower. If you’re not, ask if adding it could help.

- Keep track of symptoms. New fatigue, joint pain, rashes, or swelling after a switch could be a sign of ADA development.

- Don’t panic if your doctor says "it’s the same." It’s not. But it’s close enough for most people.

And if you’re switching back? That’s even trickier. Once your body makes antibodies, they stick around. Going back to the original might not fix it.

The future: smarter biosimilars, better tests

By 2027, experts predict we’ll be able to map the exact sugar patterns on a biologic protein with 99.5% accuracy using advanced mass spectrometry. That means manufacturers will be able to match the original with near-perfect precision - shrinking the chance of immunogenicity to almost nothing.

Meanwhile, researchers are combining proteomics, glycomics, and immunomics - looking at the protein, the sugars, and your immune response all at once. Clinical trials are already using these tools to predict who’s at risk before they even get the drug.

But for now, the truth is simple: biosimilars are not identical. And sometimes, your body knows it.

That doesn’t mean they’re unsafe. Most are safe. Most work just fine. But if your immune system is sensitive, or your condition is fragile, those tiny differences matter. And that’s why you need to stay alert - not afraid, but aware.

Are biosimilars as safe as the original biologics?

For most people, yes. Large studies and real-world data show that biosimilars work just as well as the originals in treating conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease. But safety isn’t just about effectiveness - it’s about immune reactions. While most patients experience no difference, a small percentage develop anti-drug antibodies after switching, which can reduce drug effectiveness or cause new side effects. That’s why monitoring after a switch is important.

Can you switch back to the original biologic if the biosimilar causes side effects?

It’s possible, but not always effective. If your body has already made antibodies to the biosimilar, those antibodies might also recognize the original biologic - because they’re so similar. This can lead to reduced effectiveness or allergic reactions even after switching back. It’s best to avoid switching unless necessary, and if you do switch, track your symptoms closely.

Why do some people get immune reactions to biosimilars and others don’t?

It depends on your immune system. People with autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis are more likely to react because their immune systems are already overactive. Genetics also play a role - certain HLA gene variants make you 4-5 times more likely to develop antibodies. Other factors include how the drug is given (subcutaneous shots are riskier than IV), how often you get it, and whether you’re taking other drugs like methotrexate that suppress immune responses.

Do all biosimilars have the same risk of immunogenicity?

No. Different biosimilars for the same biologic can have different risks. This is because each one is made using a unique manufacturing process. Factors like the cell line used, purification methods, and stabilizers (like polysorbate 80 vs. 20) can change how the protein folds or aggregates - and that affects immune recognition. Even small differences in sugar attachments can trigger reactions in sensitive people.

How do doctors test for immunogenicity?

Doctors use blood tests to detect anti-drug antibodies (ADAs). First, a screening test looks for any antibodies that bind to the drug. If positive, a confirmatory test checks if they’re truly specific. Then, a neutralizing antibody test sees if those antibodies block the drug from working. These tests aren’t routine - they’re usually done in research or if a patient loses response to treatment. Not all clinics offer them, and results can vary depending on the lab’s methods.

Are biosimilars cheaper because they’re less safe?

No. Biosimilars are cheaper because they don’t require the same expensive clinical trials as new biologics. They build on data from the original drug. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA require extensive testing to prove similarity in structure, function, and safety - including immunogenicity. Lower cost doesn’t mean lower safety. It means smarter development. But cost savings shouldn’t override careful monitoring, especially for patients with complex conditions.

Medications

Medications

Brett MacDonald

February 2, 2026 AT 07:07also why does my knee hurt more after switching? am i the only one?

Vatsal Srivastava

February 2, 2026 AT 08:07Ansley Mayson

February 2, 2026 AT 16:38phara don

February 4, 2026 AT 11:34Hannah Gliane

February 6, 2026 AT 03:05and you’re surprised? we let robots cook our food and still think medicine is magic. 🤡

Murarikar Satishwar

February 7, 2026 AT 18:36Dan Pearson

February 8, 2026 AT 04:53My cousin took the biosimilar for RA and ended up in the ER with anaphylaxis. You think that’s coincidence? Nah. It’s corporate greed. We’re guinea pigs.

And don’t even get me started on how they cut corners on polysorbate. That stuff’s basically poison if it’s not pure. 🇺🇸💪

Ellie Norris

February 9, 2026 AT 17:22But honestly? Most people don’t even notice. The real problem? We don’t test for ADAs unless they’re failing. And we should. Just a simple blood test every 6 months. Easy fix.

Marc Durocher

February 10, 2026 AT 01:49It’s weird how personal it is. Like, your body’s got its own opinions. Some people are chill with it. Others? Their immune system throws a rave and invites every T-cell it knows. 🤷♂️

larry keenan

February 10, 2026 AT 22:30