When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But what if the batch of generic medicine you’re holding isn’t even close to the batch used in the bioequivalence study? This isn’t a hypothetical. It’s a real, documented problem - and regulators are only now starting to catch up.

What Bioequivalence Actually Means

Bioequivalence is the legal and scientific standard that lets generic drugs enter the market without repeating expensive clinical trials. The rule is simple: the generic must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at roughly the same speed as the original. That’s measured using two key numbers - AUC (how much drug gets absorbed over time) and Cmax (how fast it peaks in your blood). The global standard, set by the FDA in 1992 and later adopted by the EMA and others, says the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of these values between the generic and brand must fall between 80% and 125%. If it does, the drugs are declared bioequivalent. Simple. Clean. But dangerously incomplete.The Hidden Problem: Batch-to-Batch Differences

Pharmaceutical manufacturing isn’t perfect. Even with strict controls, slight variations happen between batches - different mixing times, temperature shifts, drying rates, or even minor changes in raw material sourcing. These differences can affect how the drug dissolves, how fast it’s absorbed, and ultimately, how well it works. A 2016 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics found that batch-to-batch variability accounts for 40% to 70% of the total error in bioequivalence studies. That means most of the "noise" in the data isn’t from people’s bodies - it’s from the drugs themselves. Here’s the kicker: current bioequivalence tests compare one batch of generic to one batch of brand. If the brand batch used in the study happens to be unusually consistent, and the generic batch is slightly off, the test might say they’re not equivalent - even if the generic is perfectly fine. Conversely, if the brand batch is unusually variable and the generic happens to match it, the test might wrongly say they’re equivalent. This isn’t just theory. Researchers call it "confounded bioequivalence" - where the result depends more on which batches you picked than on the actual products.Why the 80-125% Rule Isn’t Enough

The 80-125% range was never meant to be a universal truth. It was a pragmatic compromise - a number that worked for most simple, well-behaved drugs like aspirin or metformin. But it breaks down with complex products: inhalers, nasal sprays, topical creams, and extended-release tablets. For example, a nasal spray’s performance depends on tiny differences in nozzle design, propellant pressure, and particle size. Two batches of the same brand product can vary enough to change how much drug reaches your nasal lining. If the bioequivalence study uses a "lucky" batch of the brand drug - one that happens to be very consistent - the test will underestimate the true variability. That means a generic that’s perfectly fine might fail the test just because it’s not identical to that one lucky batch. Dr. Robert Lionberger, former head of the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs, put it bluntly: ignoring batch variability creates "unacceptably high risks of both false-negative and false-positive findings." In plain terms: good drugs get rejected. Bad ones slip through.

What’s Being Done About It?

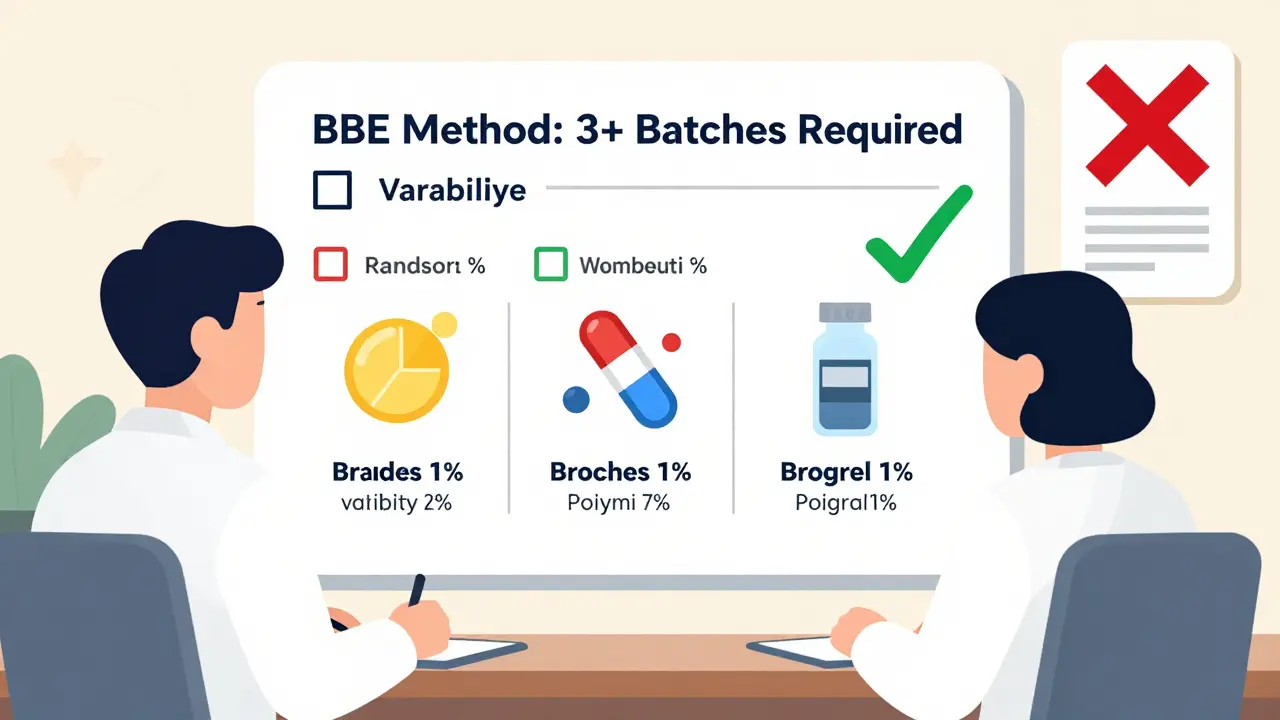

The industry has known this for years. But change moves slowly. Now, regulators are finally listening. In 2020, researchers proposed a new method called Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE). Instead of comparing the generic to one brand batch, BBE compares it to the average variability of multiple brand batches. The test asks: "Is the difference between the generic and the brand smaller than the natural variation we see between the brand’s own batches?" If the brand’s batches vary by 15%, and the generic is only 8% different from the brand average, it passes. Simple. Fair. Realistic. Simulations show that testing just three brand batches boosts the accuracy of the test from 65% to over 85%. That’s a huge leap. The FDA has already started moving. In 2022, their guidance for nasal sprays required applicants to test at least three production-scale batches of both the brand and generic. In June 2023, they released a draft guidance titled Consideration of Batch-to-Batch Variability in Bioequivalence Studies, with final rules expected in mid-2024. The EMA is doing the same. Their 2023 workshop on complex generics listed "inadequate consideration of batch-to-batch variability" as one of the top three challenges in generic drug approval. Participants agreed: the rules need updating.What This Means for Generic Drugs

Right now, most generic manufacturers still test only one batch. But that’s changing fast. A 2022 survey by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association found that 78% of major companies now test multiple batches for complex products - up from just 32% in 2018. Why? Because regulators are starting to reject applications that don’t show batch consistency. The FDA reported a 22% increase in bioequivalence-related deficiencies in generic drug applications between 2019 and 2022 - many tied to insufficient batch data. For patients, this means better quality control. Drugs that work reliably, every time. For manufacturers, it means higher upfront costs - running multiple batches, more testing, more statistical analysis. But in the long run, fewer rejections, fewer delays, and more trust in generics.

Medications

Medications

Murarikar Satishwar

February 3, 2026 AT 20:58This is such an important topic that gets ignored too often. I work in pharma logistics in India, and I’ve seen firsthand how batch variations creep in due to humidity, power fluctuations, even transport delays. The 80-125% rule is a relic. We need multi-batch testing-especially for antivirals and antiepileptics. Patients aren’t lab rats; their lives depend on consistency.

Regulators are slow, but the data is clear. It’s not about perfection-it’s about predictable variance. If the brand’s own batches vary by 12%, why should a generic be held to a 5% standard? That’s not science-it’s arbitrary math.

Dan Pearson

February 4, 2026 AT 21:53Oh wow, so now we’re going to turn every pill into a NASA mission? We’ve got people in this country who can’t even spell ‘ibuprofen’ and you want them to understand batch variability? The FDA’s got better things to do than babysit every tablet. If it’s labeled ‘generic’ and costs less, that’s all most folks care about. Stop overcomplicating things for the sake of academic navel-gazing.

Also, why do Europeans get to dictate how we make medicine? We invented this system. Let’s not turn it into a UN summit on drug chemistry.

clarissa sulio

February 4, 2026 AT 22:13I’m a nurse in rural Ohio. I’ve had patients tell me their generic seizure med suddenly made them dizzy or caused rashes-switched back to brand, problem vanished. Then the brand got too expensive, they went back to generic, and it happened again. It’s not placebo. It’s real. We need better standards, not more bureaucracy. If it saves lives, it’s worth the cost.

And no, I don’t care if it’s ‘too complicated’-patients don’t care about complexity. They care about not dying.

Solomon Ahonsi

February 6, 2026 AT 18:14Ugh. Another long-winded post about how the system’s broken. Can we just agree that generics are cheaper and mostly work? Why does every damn thing need a 10-step regulatory overhaul? I take my blood pressure med and it does the job. If it doesn’t, I switch brands. Done.

Stop making medicine into a PhD thesis. People just want to feel better, not get a lecture on Cmax variability.

George Firican

February 8, 2026 AT 10:01There’s a deeper philosophical layer here that few are touching: the illusion of uniformity in a fundamentally chaotic world. We want our pills to be perfect because we crave control over our fragile biology. But medicine-like life-is inherently variable. The body doesn’t absorb drugs the same way every day. Sleep, stress, gut flora, even the weather alter pharmacokinetics.

So why do we treat a 125% variance as a crisis, yet accept that a person’s blood pressure swings 30 points between morning and night? The real question isn’t whether batches vary-it’s whether we’re willing to tolerate human imperfection in our systems. The new multi-batch models don’t fix the problem-they acknowledge it. And that’s the first step toward wisdom, not just regulation.

Perhaps the goal shouldn’t be identical pills, but predictable outcomes. That’s not just science-it’s humility.

Vatsal Srivastava

February 8, 2026 AT 18:35Brittany Marioni

February 9, 2026 AT 09:24I want to say thank you for this incredibly thoughtful, deeply necessary breakdown. So many people dismiss generics as ‘cheap imitations,’ but this shows how deeply unfair the system has been-not just to patients, but to honest manufacturers who want to do right.

And to those who say ‘just switch brands’-what if you’re on Medicaid? What if you live in a food desert with one pharmacy? What if you’re elderly and can’t afford to try five different generics because one made you nauseous?

This isn’t just about science-it’s about justice. We owe it to every person who takes a pill to make sure it’s reliable. The FDA’s draft guidance? It’s a start. Let’s push them to make it mandatory, not optional.

Hannah Gliane

February 10, 2026 AT 06:17Wow. Just... wow. 😒 So now we need to test THREE batches of every pill? Who’s gonna pay for that? The patient? The taxpayer? Or maybe the generic companies will just raise prices and call it ‘quality assurance’?

And don’t get me started on how the FDA’s ‘draft guidance’ is basically a 50-page nap. 🥱 Meanwhile, people are skipping doses because they can’t afford the brand. You want to fix bioequivalence? Fix the pricing first. Then we can talk about your fancy statistical models.

Also, if your drug doesn’t work, maybe you’re just not taking it right. 🙄