Every time you pick up a generic pill, you’re trusting that it works just like the brand-name version. But what if the ad you saw made that promise in a way that wasn’t true? False advertising in generic pharmaceuticals isn’t just unethical-it’s illegal, and the consequences can be deadly.

What Counts as False Advertising for Generic Drugs?

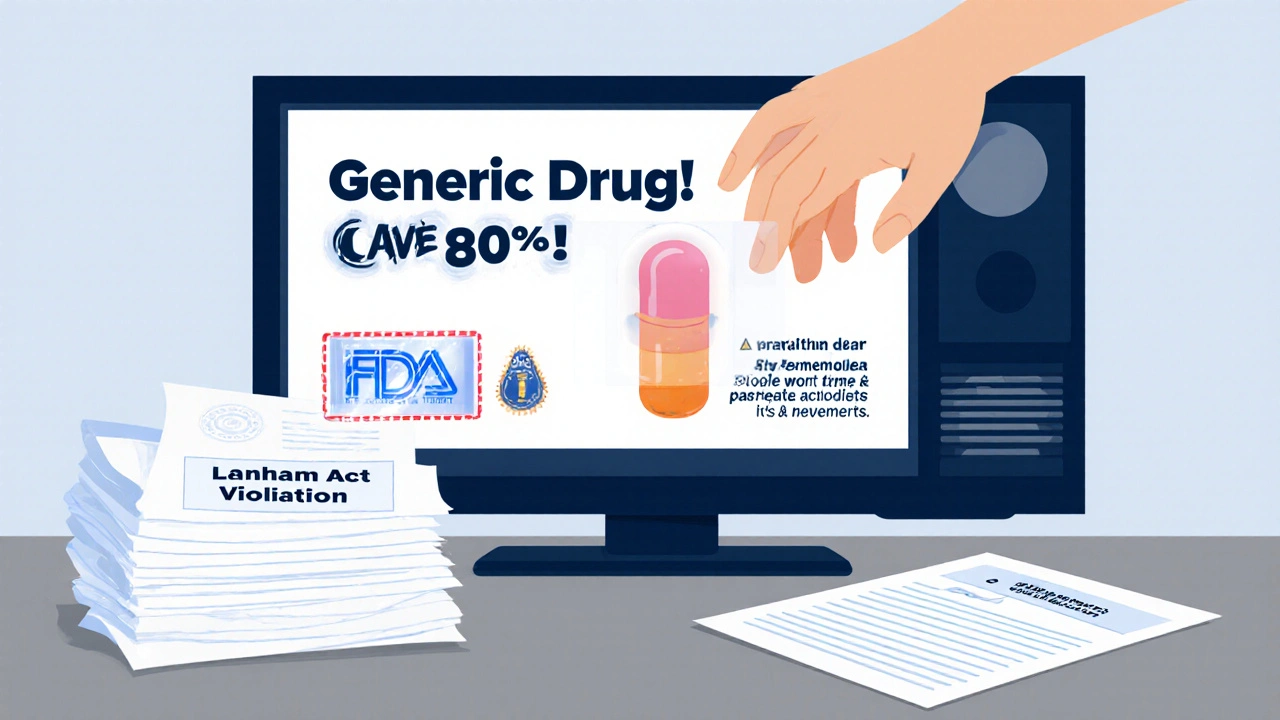

False advertising in generics happens when a company misleads people about what the drug can do, how safe it is, or how it compares to the brand-name version. It’s not just about lying. It’s about creating impressions that aren’t backed up by science. For example, saying a generic drug is "just as good" without proving it meets FDA bioequivalence standards is a red flag. Or using visuals that look too much like the brand-name pill to confuse patients. Even saying "FDA Approved" when the product only has clearance-those are real legal traps.The FDA requires generics to prove they’re bioequivalent: meaning they release the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand drug, within 80-125% of the reference. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a hard standard. If an ad implies the generic is better, safer, or more effective without head-to-head clinical trials, it’s crossing the line. And if it suggests the brand-name drug is dangerous or inferior without evidence, that’s also illegal.

The Laws That Keep Generic Ads Honest

Three main laws protect you from deceptive generic drug ads. First, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) gives the FDA power to regulate drug labeling and advertising. Second, the Lanham Act lets competing drugmakers sue each other for false or misleading claims that hurt their business. Third, every state has its own consumer protection laws-like New York’s General Business Law § 349-that let patients sue for damages if they were misled.In September 2025, the White House stepped in with a presidential memorandum ordering the Department of Health and Human Services to crack down on ads that push expensive brand-name drugs over cheaper generics. The goal? Stop companies from making patients believe generics are risky or less effective. That’s a big shift. For years, the focus was on brand-name ads. Now, the FDA is actively targeting misleading claims about generics too.

The "Adequate Provision" Loophole Is Gone

For nearly 30 years, drug companies could get away with showing only the biggest risks in a TV or radio ad-then telling viewers to "see your doctor" or "visit our website" for the full list. That was called the "adequate provision" rule. It created a dangerous gap. Patients saw the benefits, heard the headline risk, but never got the full picture. That loophole closed in September 2025.Now, every broadcast or digital ad must include all major side effects, contraindications, and safety warnings right in the message. No more hiding behind links or phone numbers. The FDA now requires risk information to appear in at least 14-point font, with high contrast, so it’s clear even on small screens. This change hits generic manufacturers hard because their ads are often cheaper and simpler. But if you’re skipping the full risk disclosure, you’re breaking the law.

What Generic Ads Can and Can’t Say

Here’s what’s allowed and what’s not:- Allowed: "This is a generic version of [Brand Name]." "Lower cost alternative." "FDA-approved for the same use as [Brand Name]."

- Not Allowed: "Our generic works better than the brand." "The brand causes liver damage-our version doesn’t." "FDA Approved" if the product is only cleared under an ANDA (Abbreviated New Drug Application)."

Even saying "equivalent" without adding "bioequivalent" can be risky. The FDA doesn’t use "therapeutic equivalence" for all drugs-especially narrow therapeutic index drugs like levothyroxine or warfarin. For those, even tiny differences matter. Ads that imply you can swap them freely without a doctor’s approval are setting patients up for harm.

And don’t think visual tricks are safe. Using similar colors, shapes, or logos to mimic the brand-name product? That’s been the basis of multiple lawsuits under the Lanham Act. The courts don’t care if you didn’t mean to confuse people. If a reasonable patient could mistake one for the other, you’re liable.

Who Gets Hurt When Ads Are False?

Patients pay the price. In 2024, the FDA reviewed 1,247 patient complaints tied to misleading ads. Thirty-two percent of those patients stopped taking their medication because they believed false claims-like generics were unsafe or unreliable. Many ended up back in the hospital. One Reddit thread from March 2025 showed patients refusing levothyroxine generics because of ads claiming they caused thyroid crashes. The FDA has confirmed those generics are bioequivalent. But the fear stuck.Meanwhile, seniors who saw clear, compliant ads reporting cost savings saved an average of 78% on their prescriptions. That’s the power of honest advertising. But when companies use fear, confusion, or false superiority claims, they don’t just lose customers-they risk lives.

Legal Risks for Companies

The penalties are serious. Under the Lanham Act, a competitor can sue for treble damages-three times the actual harm. The FTC can fine up to $50,000 per violation. State laws like New York’s can add another $1,000 per violation, multiplied by the number of ads. And the FDA doesn’t just issue warnings anymore. In September 2025, they sent out approximately 100 cease-and-desist letters targeting deceptive generic ads and thousands of warning letters overall.Major companies like Teva and Sandoz have already paid millions in settlements for misleading claims. Smaller manufacturers are especially vulnerable. Without a dedicated legal and regulatory team-typically 15 to 25 people-compliance is nearly impossible. The average cost of compliance for a top generic maker is $2.1 million per year. But skipping it? Could cost you $3 billion, like GlaxoSmithKline did in 2012.

How to Stay Compliant

If you’re marketing a generic drug, here’s what you need:- Work with a regulatory affairs specialist with at least five years of FDA experience.

- Have legal counsel review every ad for Lanham Act and state law risks.

- Include all major risks directly in the ad-no "see website" shortcuts.

- Use only approved language: "bioequivalent," not "identical" or "better."

- Never imply superiority without clinical proof.

- Clearly state the reference brand name and that this is a generic.

- Test visuals with real patients to ensure no confusion with the brand.

Compliance isn’t optional. The FDA’s 2025 crackdown shows they’re watching. And with draft legislation like H.R. 4582-the "Transparency in Drug Advertising Act"-coming next year, the rules will only get tighter.

What’s Next for Generic Drug Advertising?

Expect more coordination between the FDA and FTC. They’re moving toward one standard for risk disclosure across all media-TV, radio, social, print. That means no more patchwork rules. And enforcement is rising. Evaluate Pharma predicts a 35% annual increase in legal actions through 2027, with generics under the most scrutiny.Companies that invest in compliance-like Pfizer’s $45 million internal review system-are staying ahead. Those cutting corners? They’re playing Russian roulette with lawsuits, fines, and public trust. The market for generics is $140 billion. But the cost of getting it wrong? It’s not just financial. It’s human.

Can a generic drug be advertised as "FDA Approved"?

No. Generic drugs are approved under an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), which is different from the full New Drug Application (NDA) used for brand-name drugs. Saying "FDA Approved" without context implies the same review process as the brand, which is misleading. The correct phrasing is "This generic drug is approved by the FDA for the same use as [Brand Name]."

Is it illegal to say a generic drug is cheaper than the brand?

No, but you can’t claim specific savings unless you have hard data. Saying "lower cost" is fine. Saying "save 80%" requires documented pricing data from pharmacies and must be verifiable under FTC guidelines. Vague claims like "huge savings" are risky and can trigger investigations.

What happens if a patient stops taking a generic because of a false ad?

If the ad misled them and they suffered harm-like a seizure from stopping seizure medication, or a stroke from stopping blood thinners-they can sue under state consumer protection laws. The FDA documented over 400 cases in 2024 where patients discontinued generics due to fear from misleading ads, leading to hospitalizations. Those cases are now being pursued in court.

Can generic manufacturers use the same logo or color as the brand?

No. Even similar shapes, colors, or logos can be considered confusing under the Lanham Act. Courts have ruled in multiple cases that if a reasonable patient could mistake the generic for the brand-or believe they’re the same product-the ad is deceptive. Generic pills must be visually distinct to avoid consumer confusion.

Are all generic drugs bioequivalent?

Yes, by law. Every generic approved by the FDA must demonstrate bioequivalence to the brand-name drug within 80-125% of its pharmacokinetic profile. But not all generics are therapeutically equivalent. For drugs with narrow therapeutic indexes-like levothyroxine, digoxin, or warfarin-small differences can matter. That’s why doctors sometimes require authorization before switching. Ads that ignore this distinction are misleading.

What’s the difference between bioequivalence and therapeutic equivalence?

Bioequivalence means the drug enters the bloodstream at the same rate and amount as the brand. Therapeutic equivalence means it’s expected to work the same way in the body with the same clinical effect. All generics are bioequivalent, but therapeutic equivalence is only assigned by the FDA for certain drugs. Ads that treat them as the same thing are violating FDA guidelines.

Medications

Medications

Manish Pandya

November 25, 2025 AT 19:03Just had to share this with my grandma who’s been on levothyroxine for 15 years. She switched to a generic last year after reading this exact info and now saves $40/month. No issues. People need to stop letting fearmongering ads scare them out of affordable meds.

Real talk: if your doctor says it’s safe, trust them. Not some sketchy YouTube ad with a guy in a lab coat yelling about "toxic generics."

Lawrence Zawahri

November 26, 2025 AT 04:36THIS IS A COVER-UP. The FDA is in bed with Big Pharma. They let generics through with 80% bioequivalence? That’s not a standard-that’s a death sentence waiting to happen. You think they care about you? They care about profit. The real reason they cracked down on ads? Because people are starting to notice the pills don’t work the same. They’re poisoning us slowly. And now they’re silencing the truth with "compliance" nonsense. Wake up.

They’ve been hiding this since 1998. The WHO knows. The EU knows. But you? You’re still swallowing the lie.

🔍 #FDAcorruption #GenericsArePoison

Benjamin Gundermann

November 26, 2025 AT 22:37Okay so let’s unpack this real quick, because I’ve been thinking about this since I saw my cousin’s prescription bill go from $300 to $60 and I was like… wait, is this gonna kill her?

Look, I get it. Big Pharma wants you to think generics are trash. But honestly? The whole system is rigged. The FDA doesn’t test every batch. They test one from a factory in India that’s owned by the same parent company as the brand-name maker. So technically it’s "bioequivalent" but… are we really talking about the same molecule? Or just the same label?

And don’t even get me started on the color thing. I’ve seen generics that look *exactly* like the brand, just with a different name printed on it. That’s not marketing-that’s psychological manipulation. You think your brain doesn’t register "this looks like my old pill" and feel safer? Yeah, it does. And that’s intentional.

So yeah, the rules are clear. But the system? Nah. It’s still a circus. And we’re all clowns holding our prescriptions like they’re holy water.

Also-why does every generic have that weird chalky taste? The brand didn’t. Coincidence? I think not.

TL;DR: I’m not saying generics are bad. I’m saying we’re being played. And someone’s making bank off our confusion.

Rachelle Baxter

November 27, 2025 AT 09:40OMG THIS IS SO IMPORTANT 😭

Like… I can’t believe people still fall for "FDA Approved" on generic ads. That’s like saying "this car is safe" because it has seatbelts… but ignoring the fact that the engine’s held together with duct tape. 🚗💥

And the visual mimicry?! That’s not just unethical-it’s predatory. Imagine being elderly and seeing a pill that looks *exactly* like your old one, but it’s a different strength. You take it. You have a stroke. And then you find out the company knew the color was too similar. 😡

Also, why is no one talking about how these ads target seniors? They’re the most vulnerable. They trust labels. They don’t read the fine print. And now they’re being manipulated with fake safety claims. This needs to be on the news. Like, NOW.

#StopGenericMisleadingAds #PatientsDeserveTruth

Dirk Bradley

November 28, 2025 AT 05:56The regulatory framework governing pharmaceutical advertising is, in theory, robust. However, the enforcement mechanisms remain woefully inadequate to address the systemic incentives for deceptive marketing. The Lanham Act, while ostensibly a tool for competitive redress, is often rendered impotent by the prohibitive cost of litigation. Furthermore, the FDA’s cease-and-desist directives lack sufficient punitive teeth to deter repeat offenders. The recent presidential memorandum, while symbolically significant, does not constitute structural reform. Without mandatory third-party audit trails for advertising claims, and without real-time monitoring via AI-driven surveillance of digital ad platforms, compliance remains performative rather than substantive. One must conclude that the current regime is a façade-designed to project accountability while permitting exploitative practices to persist under the guise of regulatory compliance.

Emma Hanna

November 29, 2025 AT 17:12Wait-so you’re telling me that companies are allowed to use the same colors, shapes, and logos as brand-name drugs?!!! That’s not just wrong-it’s criminal.!!! People die from this.!!! I had an aunt who took the wrong pill because she thought it was her brand-she ended up in the ICU.!!! And now you’re telling me this is still happening?!?!?!?!!!

Mariam Kamish

December 1, 2025 AT 06:58Y’all are overthinking this. 🤡

Generic = cheaper. Brand = expensive. That’s it.

Most people don’t even notice a difference. If you do? Switch back. Stop making this a drama.

Also-why are we still talking about this? The FDA already said it’s fine. Move on.

Adesokan Ayodeji

December 2, 2025 AT 00:45My brother is a pharmacist in Lagos, and he tells me the same story every week: people come in terrified because they saw an ad saying generics cause seizures. But when he checks the batch, it’s FDA-approved, properly labeled, and bioequivalent. He spends hours calming patients down.

Here’s the truth: in countries where generics are trusted, healthcare costs drop by 60%. In places where fear rules? People skip meds. They get sicker. They die. And it’s not because the drug failed-it’s because the ad lied.

So if you’re a manufacturer? Don’t be greedy. Be honest. If you’re a patient? Trust your doctor, not a 15-second TikTok ad. And if you’re a regulator? Stop waiting for bodies to pile up before you act.

We can do better. We’ve done better. Let’s not go backward.

Stay safe. Stay informed. And please-stop letting fear sell pills.

Karen Ryan

December 2, 2025 AT 19:29This is such an important topic, especially for immigrant families. My mom came from Mexico and refused to take her generic blood pressure med for a year because she thought it was "fake." She believed the brand-name one was "real medicine."

When I showed her the FDA bioequivalence data in Spanish, she cried. Not because she was scared-but because she realized she’d been scared for nothing. She’s been taking the generic for 3 years now. Her BP is better than ever.

Language matters. Cultural context matters. And so does trust. We need ads that don’t just follow the law-but honor the people they’re speaking to.

Thank you for writing this. It’s not just legal-it’s human.

Kaylee Crosby

December 4, 2025 AT 15:32I work in a pharmacy and I see this every day. People panic because they think their generic doesn’t work. But 9 times out of 10, it’s because they didn’t take it consistently or they changed their diet or they’re stressed.

My advice? Don’t blame the pill. Blame the fear.

And if you’re a company making ads? Stop being lazy. Just say what it is. Generic. Same active ingredient. Lower price. Done.

People are smart. They just need clear info-not hype.

Also-seriously, stop copying the pill color. It’s 2025. We have printers. Make it different. It’s not hard.

Terry Bell

December 5, 2025 AT 15:47So like… if a generic looks like the brand but says "approved under ANDA" instead of "FDA approved" is that still a problem? I mean… isn’t that just semantics? Like saying "I’m a doctor" vs "I’m a medical doctor"? But then again… I guess when your life’s on the line, semantics matter a lot huh.

Also I think we need to stop treating pills like they’re magic. They’re chemicals. They’re not gods. If your body reacts weirdly to one brand vs another? Maybe it’s your gut. Maybe it’s your stress. Maybe it’s the filler. Not the active ingredient.

But yeah… don’t copy the color. That’s just rude.

Patrick Goodall

December 5, 2025 AT 17:05THEY’RE LYING TO US AGAIN. The FDA’s 80-125% range? That’s a 45% swing in blood concentration. That’s not equivalent-that’s a gamble. And the fact that they let companies use the same colors? That’s not a loophole. That’s a trap. And now they’re pushing this "transparency" nonsense like it’s a win? Nah. It’s PR.

They’ve been doing this since the 80s. They’ll never admit it, but generics are a controlled experiment on the public. And guess what? The data’s not public.

Who benefits? Big Pharma. Who pays? You. Me. Grandma. The kid with asthma who can’t afford his inhaler.

They want you to think this is about ads. It’s not. It’s about control.

And if you believe otherwise? You’re part of the problem.

Jacqueline Aslet

December 6, 2025 AT 14:00The entire premise of this piece is predicated upon a fundamental misapprehension of the FDA’s regulatory philosophy. Bioequivalence, as codified in 21 CFR § 320.1, is a pharmacokinetic standard-not a therapeutic one. To conflate the two is to commit a category error of significant consequence. Furthermore, the Lanham Act was never intended to serve as a vehicle for consumer protection; its jurisprudential roots lie in trademark dilution and commercial disparagement. To repurpose it as a public health instrument is a legal overreach of considerable magnitude. The recent enforcement actions, while politically expedient, lack doctrinal coherence and risk destabilizing the delicate balance between innovation and access that has sustained the generic drug market for over four decades. This article, though well-intentioned, is an exercise in rhetorical populism masquerading as regulatory analysis.

Benjamin Gundermann

December 6, 2025 AT 21:33Wait, so if I’m reading this right… the FDA doesn’t even require generics to be tested against the *brand* in every batch? They just test against their own internal standard? So if the brand changes its formula next year, but the generic doesn’t update? It’s still "bioequivalent"… but now it’s not equivalent to the actual drug people are supposed to be matching?

That’s not regulation. That’s a loophole with a fancy name.

And the fact that the FDA didn’t even mention this in the 2025 memo? Yeah. That’s not oversight. That’s negligence.